|

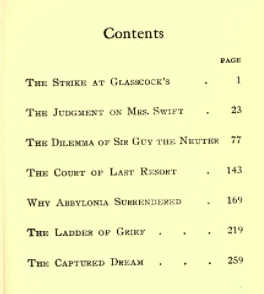

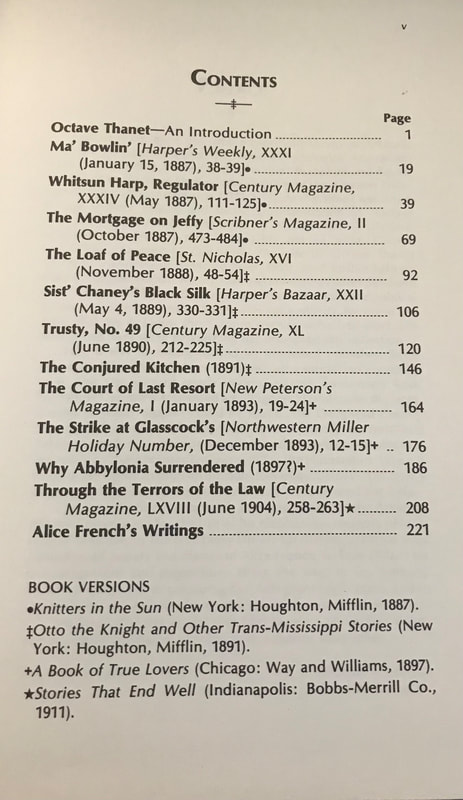

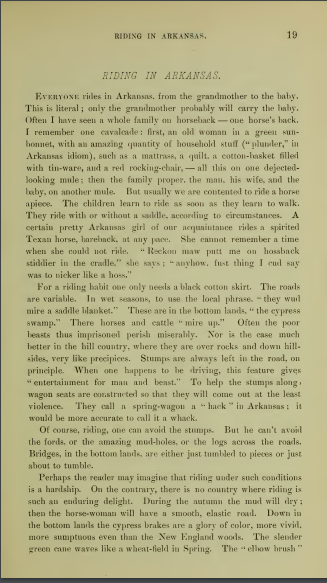

It's been a bit, I know. Part of the reason is the chaos that was 2022 for me. We decided to sell the house and move, and I decided to go back to school. On top of all of that, I cleaned off my trusty laptop in the spring and lost my progress on editing The Dalrymple Mystery, and I didn't have the focus to go back to that project. When I lost my files, I also deleted the original PDF with the images from the serialized version. That piece took several steps to create. My first thought was that I was going to have to go back through all issues of The National that contained excerpts and find the images. Then, I remembered that I have the PDF file on my Nova Air and was able to move it to the Google Drive. Crisis averted! I just finished capturing the five drawings that go with the story, along with their original captions, so I can include those in the complete version of the story. A Book of True Lovers My last entry was almost a year ago, and I shared my highlights and notes file for this collection. I revisited McMichael's comments about this collection, and was not surprised to find he has little to say about it on page 153: A Book of True Lovers came out at a time when editors were pleased to take anything she wrote. Her income from writing had increased almost $2,000 over two years before. The sales she listed in her ledger at the end of 1897 totaled $5,390 for this year. Much of the money went toward the restoration of the house in Arkansas, which was finally being completed during summer of 1897. Alice and Jenny named their new home 'Thanford' for Thanet and Crawford. So, there is an Arkansas connection there, if only that the money was used to restore the house in Clover Bend. "The Strike at Glasscock's" was, according to McMichael, "based on an incident described by Colonel Tucker of Clover Bend and was a parable for labor, showing the plight of a rural Arkansas mill owner whose wife had gone on strike" (152-3) to get the house painted. The story is reminiscent in some ways of Mary Wilkins-Freeman's oft-anthologized "The Revolt of Mother." As such, it might be interesting in that regard. Thanet's story originally appeared in December 1893's edition Northwestern Miller Holiday Number as "The Labor Question at Glasscock's." Mary Wilkins Freeman's story appeared in print in 1890 in Harper's. Given that Thanet also published in Harper's during the late 1800s, it is likely she was familiar with the story. McMichael also discusses the relative domestic harmony at Thanford when discussing the book, which is sweet. The introduction of A Book of True Lovers is interesting, as well, as the focus there is on how all of the stories are focused on married couples. Perhaps it was a tip of Thanet's hat to the fact she valued her own Boston Marriage with Jane Crawford. A Slave to Duty & Other Women As with A Book of True Lovers, Thanet's next collection lacks much depth, despite the eye-catching title. Another volume, A Slave to Duty and Other Women, her ninth book in eight years, also appeared in 1898, a reprinting of stories gathered from a wide variety of magazines and published by Herbert S. Stone in Chicago. For the first time, critical response to her work was almost wholly uncomplimentary, the reviewers announcing that the stories were trivial and unimportant (McMichael, 158).

0 Comments

Entry coming soon. I read this in early 2022 and highlighted but need to revisit the collection now that we've moved and I located my copy of McMichael.

Link to the notes on Google Drive (highlights)

In 1895, Alice's investments paid high dividends and her writing earned her more than $3,600. Henry Mills Alden had bought a short story, "The Missionary Sheriff," for $620, the most she had ever received for a story, and it was her first to be published in Harper's Magazine. Shortly after it was accepted, Harper and Brothers sent a letter asking that she write a series of short stories to be published first in Harper's Magazine and then to be issued by the publishing house in a single volume in 1897. --McMichael, p. 145.

Individual Story Notes:

Basic Summary: Cecil Raimund goes to Arkansas to the Seyton Plantation to spend time with his twin cousins Alan (Ally) and Sally. In the two weeks covered by the novel, Cecil helps the twins solve the mystery of the KKK scaring people. It turns out that Dawsey has been counterfeiting for the last five years, and while they suspect he's the one parading as the KKK, it turns out that Aunt Valley, a local conjure woman, and Larry, Dawsey's nephew, pretended to be KKK hoping it would lead to Dawsey being arrested for moonshining or lynched by the black people in the area. The book is very much a "juvenile novel" as McMichaels indicates, as the kids are the ones who solve the mysteries. Larry confesses to the trickery after Dawsey is dead because Dawsey accused Cobbs of conspiring with him to ride as the KKK as he's dying. There is some discussion in the novel of whether Cobbs is racist, which adds some credibility to Dawsey's "confession." Ultimately, the truth is revealed and things are tidy and neat for the most part--the kids are rewarded. Larry gets to live with Cobbs, Ally and Cecil become the best of friends (in a mirroring relationship of the one between Raimund and Seyton), and Sally gets $500 for her shrewd detective work. The Title: The title is echoed in two passages in the book. First, by Colonel Seyton after things have calmed down and Cobbs is no longer under suspicion. Basically, Seyton praises everyone involved in the resolution of the story, not just his own children (although Sally is the best detective of them all). "'This is just in time for a toast,' said he. 'Cobbs, here's your glass, man. 'WE ALL, East AND WEST, NORTH AND South! To our better acquaintance, because that means to our better and closer and dearer friendship.'" (Thanet, p. 271). Cecil, being from Chicago, thinks of himself as a northerner and spends the early parts of the novel thinking that his Arkansas cousins are simple and poor. He assumes he can better them at just about everything, including hunting. During a hog hunt he and Ally are not supposed to be on, Cecil faces a wild boar and thinks he can kill it with his revolver. Cobbs and Ally shoot the boar before it can get to Cecil, and he's humbled by it. Ally assures him that had they not intervened, Cecil surely would have felled the hog himself. The final paragraph of the book echoes the title and is reminiscent of the hog hunt, as well as the solving of the mystery and Cecil growing up. "Meanwhile, it is like Cis, who is fond of trinkets and dunnery, to wear a fob-seal, on which is engraved a wild boar's head and the letters 'W. A.'. The head is a reminiscence of another hog-fight, where Cis did kill the boar, and the letters stand for WE ALL." Overlap with Expiation:

I'll be using this post and updating it throughout the project. Specifically, here you will find links to notes showing Thanet's use of specific racist language. I'll provide highlights of the text, as well as brief notes (who uses the term, how it's used).

Note: these are my highlights in Google Books. I've done minimal editing, so there may still be some spacing errors. But, these might be helpful in terms of seeing themes and isolating quotations if you're looking for certain keywords or themes. Also, note that the highlights may not be complete--for instance, my highlights for Knitters in the Sun start with "Father Quinnailon's Convert." I will add to this list as I go.

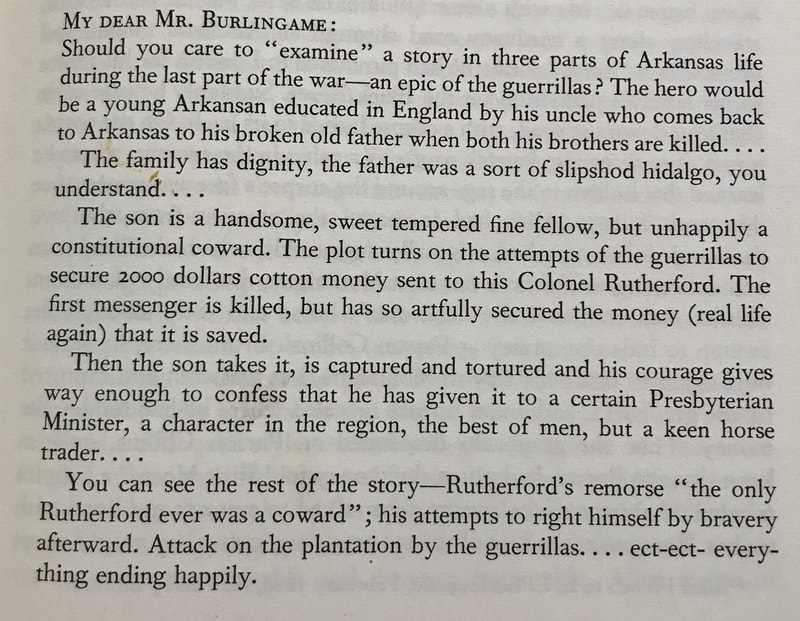

The summary in the above letter is spot on; the novel focuses on young Fairfax Rutherford, who has been living abroad with the uncle he was named for. He returns to his father's plantation in Arkansas and is immediately caught up on the robbery scheme and captured. His shame happens when he first reveals Parson Collins has the money; he feels guilty about revealing that, but is even more horrified when he thinks he's shot Collins after being burned with hot coals from the fire. The story works itself out; we later find that Collins is not only alive, but also that it wasn't Fairfax who shot him after all--it was Lige, who was aiming for Dick Barnabas, leader of the guerillas. Setting: The area around the Montaigne Plantation on the Black River. McMichaels notes it is set in 1864 (p. 118). Characters:

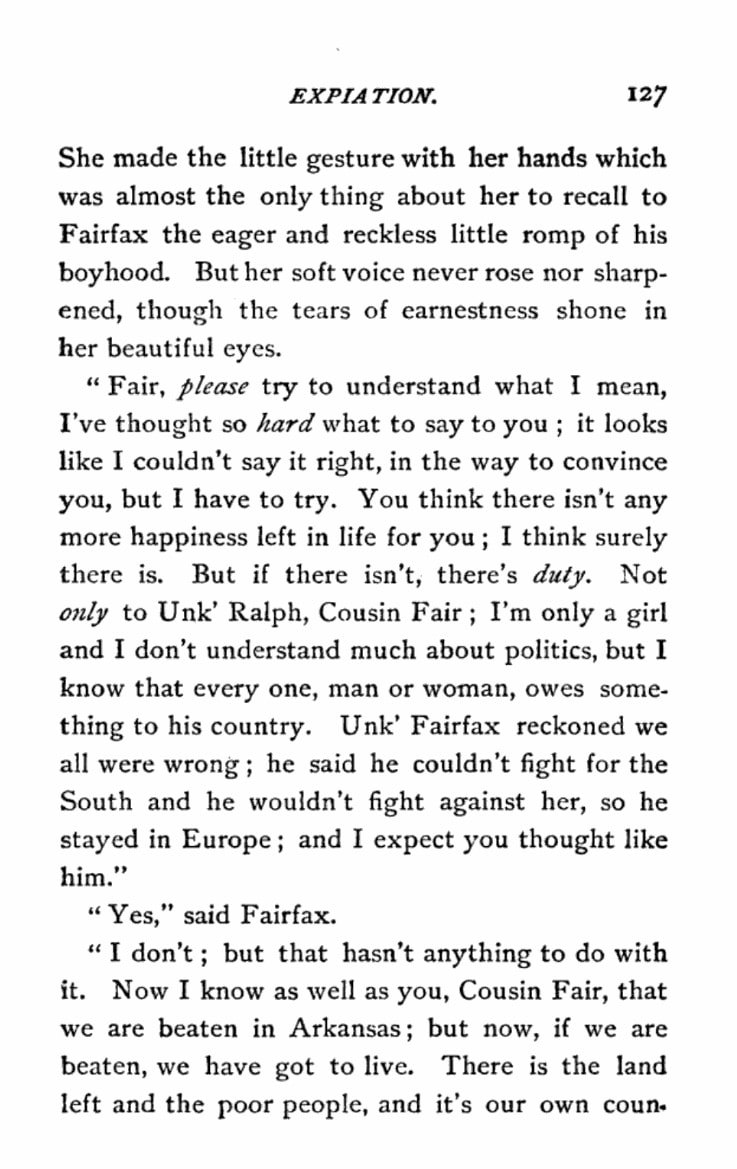

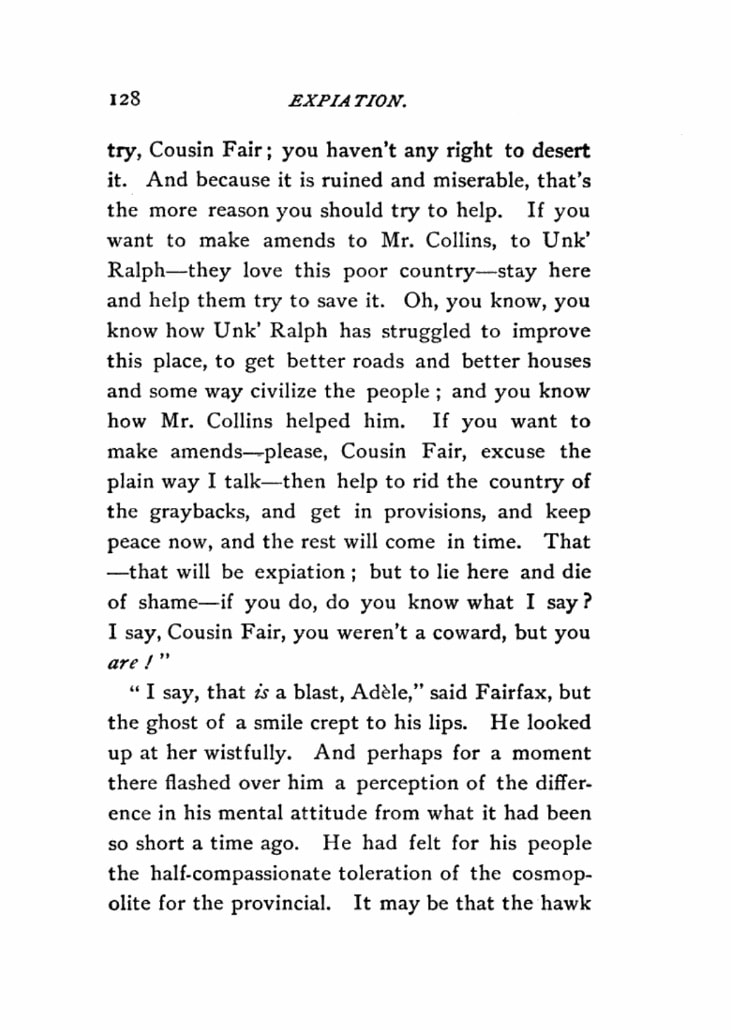

Expiation: Adele is the first to use the word "expiation" when talking to Fair about his guilt: "God won't hold you guilty for that. And even say you were guilty, guilty of the worst--well, what then? Does repentance mean despair or expiation? 'Bring forth fruits,' the apostle says, God will not despise a broken and a contrite heart: but if such a heart doesn't lead us to do something" (Thanet, p. 126). Adele continues on pages 127-128 to tell Fairfax he should stay in Arkansas and do right by Parson Collins: "you haven't any right to desert it. And because it is ruined and miserable, that's the more reason you should try to help. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country--stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country-stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends--please, Cousin Fair, excuse the plain way I talk--then help to rid the country of the graybacks, and get in provisions, and keep peace now, and the rest will come in time . That —that will be expiation; [emphasis mine] but to lie here and die of shame—if you do , do you know what I say? Cousin Fair, you weren't a coward, but you are!" Masculinity: This is a central theme as Fairfax feels the need to fit his father's image of a real man. His brothers have died, and Fairfax is the sole heir left. When Barnabas says he was a coward, it crushes Fairfax and makes the relationship with his father strained (until the truth comes out). Fairfax is a bit of a dandy, but not necessarily in a bad way. While he has funny clothes and is softer than men in the Arkansas Swamps, those traits are not seen as a failing. At the end of the novel, his refinement is mentioned and becomes a bit of an issue for Adele who thinks she can never be quite refined enough for him, but Adele winds up liking his sense of fashion and his cleanliness. On page 81, we see that Fairfax was always sensitive to fear and that even as kids Adele had a stronger sense of rationality--see below regarding childhood tales of conjure men and headless cats. Adele didn't believe they were real, but Fairfax did. Race: Aunt Hizzie: She's treated as a caricature. "Aunt Hizzie, in her white turban (economically made out of a castaway flour-sack ), with a blue apron try ing to define a waist for her rotund shape, was always a figure in the gallery when dinner was under way" (Thanet, p. 30), Her method of communication is to holler at people. Barnabas: This issue comes up not only with Hizzie and other enslaved people of color in the book but also in terms of Dick Barnabas who is described as having a "sharp profile with thin lips, curved nose, hollow cheeks, a sweeping mustache, and inky locks of hair, straight and coarse enough to warrant the common taunt that 'all of Dick Barnabas wasn't Jew was mean Injun'" (Thanet, p. 66). Early on, Colonel Rutherford is telling his wife the story of Ma'y June and says, "Dick, he was renting of me then, am - mean Jew Injun, same like he is now, and getting most his livelihood swapping horses" (Thanet, p. 41). Thanet contrasts Barnabas and Fairfax: "Their eyes met; the cruel old-race black ones, the frank brown eyes of the Anglo-American; the glitter in each crossed under the torch-rays like sword-blades , but it was the brown flash that wavered" (Thanet, p. 75). Also, Thanet uses the word "injun" again when Lige tells Sam "he had a mind to kick, but he warn't no injun, by ____" (Thanet, p. 78). "in spite of his seeming apathy, Dick's Indian blood was at boiling-point. Lige stood in front of the open window; before he had time to realize the situation he found himself sprawling on the ground outside" (Thanet, p. 92). Magic of the Swamps: Mose has freedom to travel the swamps and communicates with animals. The homestead of the French LaRouge who was killed by Barnabas and his men is the "magical" and haunted spot that Barnabas uses as home base: "on the mound to the right , which was a forgotten chief's last show of pride , an old Frenchman had built him a log cabin , where he lived alone" (Thanet, p. 77). . . "Dick told them that he chose the place because it was a spot held accursed and haunted" (Thanet, p. 78). Conjuring is mentioned when Fairfax remembers tales he was told as a child to keep him in line: "How they terrified him! That one, of the big conjure-men who threw lizards into Mammy's mother so that she died-but that was not so frightful as the one about the little black cat without a head that would come and sit by a 'mean' boy's bed and purr and purr; and , if the boy should make the least bit of noise, would leap on the bed and rub its dreadful neck against him. What a ghastly fancy! Why must he remember it now?" (Thanet, p. 81). The "now" in question is when Barnabas takes him to LaRouge's ruins. "Aunt Tennie Marlow was well enough known to Fair. She was an old and very black negress who enjoyed a great name as a bone-setter, knew a heap' baout beastis,” ushered all the babies of the neighborhood into the world, and on the strength of these gifts and of living alone was suspected to be a “conjure woman" (Thanet, p. 163). To view all of my chapter summaries and highlights, click here.

Basic summary: The story opens with one-armed Jeff Griffin carrying home a tiny coffin for the recently dead baby of Cap'n Bulah, the love of his life (and distant cousin). Bulah is the widow of Sam Eller (the baby's father). Bulah still runs his boat, as she is determined to pay off his debts. When her baby dies, she is inconsolable. On his way to show her the coffin, Jeff picks up Nate who tells him about a baby left at the plantation store. The widow Mrs. Brand is caring for the baby, and Jeff picks her up and takes her to his house where Bulah is still rocking her dead child. When he sets the boy on the floor, he cries for his mother and Bulah shakes herself out of her stupor, allowing her own baby to be buried. Jeff and Bulah begin to care for the child in February. In October his mother, a traveling cotton picker, returns and demands her child back. The widow Brand saves the day when Headlights (real name Sabrina Mathews) tries to force the sheriff to tear the boy--now called Jeffy--from his foster parents. She demands board, cost of clothing, and cost of housing for the last eight months at a total of $27 to be paid in six months or Jeff and Bulah retain custody forever. Mr. Francis draws up a contract--thus, the "Mortgage on Jeffy." Headlights demands the right to pay the debt early. She returns when Jeffy has come down with a fever and they fear he'll develop pneumonia. He's always been puny, which was one of the reasons they refused to let her take him, as he would die without care he needs--care his mother can't give him on the road as part of a cotton-picking team. Jeff sees her in a stupor in the swamp and takes her home with him. Headlights realizes that she can't care for the child properly and makes Jeff and Bulah agree to marry and they can keep him. She develops pneumonia and dies. Before she does, she pulls a leather pouch from her neck and says it is for Jeffy. Inside is the $27 and a copy of the mortgage. Notes: I'm intrigued by the name "Headlights" here. It seems really odd. Also, I am not sure that this is as clearly sentimental or classist as McMichael seems to think. Headlights, just as with Dosier and Chaney before, has deep emotional feelings and ties to her son, even as she leaves him at 17 months at the store. Carrying a child that small from job to job couldn't be easy, and likely the child would have died. The whole mortgage situation is also weird. Obviously, Jeffy is not a slave or treated as property by Bulah and Jeff, but the idea of owning other people is definitely at play here. There's some weird "owning you to take care of you" stuff going on here (as in, you're being treated as property for your own good).

Basic summary: This is an oddly cute story about a Governor at home who is approached by the mother of Fritz Jansen, a man sentenced to hang for the murder of his fiancee. The woman is German and speaks very little English. Luckily, the Governor's wife, Annie, is fluent in German. The woman tells of walking 15 miles to get to him before her son's execution. She asks for a pardon, as her son is a good man who would never do such a crime. Annie pleads with her husband to stay the execution--if he's truly guilty, why not give him a life sentence so his mother doesn't suffer. The Governor counters that to do so would be worse for Fritz's mother than executing him. If she hates the Governor, Very well , so be it . She will still have her memories of his youth to console her, and her very conviction of the injustice of his fate will be a comfort to her; while, on the other hand, if I release him, he will dissipate all her illusions, neglect her, ill-treat her, very likely spend every cent of her hard earnings, and at last convince even that trusting soul what a brute he is. It is the truest kindness to her to refuse." (Thanet, 299) The day after Fritz is hanged, the mother returns with her son, Fritz. It turns out there were two men with the same name, and her son was never arrested. Because he doesn't want to share the name with such a bad man, Fritz and his mother come to the Governor for a name change. Annie declares he'll change the name as a wedding gift to Greta and Fritz. The wedding is briefly described and the story ends with Annie and the Governor relieved at the outcome.

In the end, the Governor makes the comment that he would have been so embarassed if he'd followed Annie's "feminine" mind and pardoned the evil Fritz. He asks her who was right, and she exclaims, "Both of us" (Thanet, p. 299).

Basic Summary: Milt Bedford plans to take over Sycamore Ridge's post office and oust the former northerner named Captain Leidig, the current Postmaster. General Throckmorton can't bring himself to break the news to Leidig that he is being replaced. That night, the Great Fire breaks out, and Leidig and his "chemical engine" (Thanet, p. 273-4) save the post office and the town from the blaze. Leidig is gravely injured in the fire, and Throckmorton and the town think there is no way Leidig will be removed from his post after saving everything. Unfortunately, Bedford is installed as postmaster as Leidig is on bedrest and dying. His former assistant, Roz Miller, keeps up the charade that Leidig still holds the post, unable to break his heart as he lay dying. When Bedford intercepts a note to the office by Leidig before his assistant can, he goes to visit the ill-man whose job he took. He's tender-hearted enough to continue the charade and spares Leidig's feelings. The title of the story comes from General Throckmorton, the district's congressman. While citizens discuss how wonderful Leidig is as postmaster and how it's a shame he lost the post, Throckmorton says Leidig was an idiot to start with. Not only was he a humane officer in the military who treated political opponents well (Throckmorton being confederate military), but he also was brilliant and had patents. Had he kept inventing, he would have been rich. Instead, he was an idiot: Now I , gentlemen," said Throckmorton,“ I call Hiram Leidig a plumb idiot.” The crowd simply gasped; Throckmorton being Leidig's closest friend, and a man not to desert a friend under stress of weather, "Yes, gentlemen, a plumb idiot,” he repeated, in his gentlest tone; “here he is. He could have made a fortune had he stayed in the manufacturing business. When the war broke out he was getting a salary of twelve hundred dollars, and he had invented half a dozen little tricks, and got patents on them, and saved ten thousand dollars. . . Well, what does the government or the party give Leidig for his long services? You all know. Half a dozen times he has been within an ace of getting bounced by one party or the other, and now he is going to be pitched out in good earnest by his very own party because he can't be trusted to run the office as a party machine, and Milton Bedford can! That's the size of it. Now, a man who will squander his chances of fortune and the best years of his life on a government or a party which kicks fidelity every time is - a plumb idiot!" Themes: The North is not always the enemy and service is more important than wealth. We later find that Throckmorton "loved Leidig. The two men had been like brothers since the Federal soldier saved the Confederate soldier's life and cared for him in prison during the war" (Thanet, p. 268). When he confronts Leidig about his service and how he should have stayed in business, Leidig responds by saying: Look here, Marion, the way you felt for the South, I felt for my country, our country. [bold mine] And I had this kind of a feeling: the way to obliterate the war is to fetch people close together . You stay here awhile, old fellow,' says I, “and do your best for the old flag. Be a decent fellow, for they are going to sample the North by you. Don't go at them ramping and roaring, and shaking your opinions in their face like a red rag, when they're just naturally sore all over. Here's a chance,' says I, “ to do your country better service than you did in the war" (Thanet, p. 272). The story ends with the narrator suggesting that maybe Leidig was right about how it is an honor to serve, or "perhaps, again, he may be right some day" (Thanet, p. 284).

Notes: Roz Miller always takes Christmas week off, as he is "obliged" to get drunk that week. Leidig tells him that it's improper for a postman to be drunk, so every year, he suspends him that week. To keep up the ruse while Leidig is dying, he stays sober. We find out he also has a wooden leg, which is never explained, but French did later lose a leg due to complications from diabetes and was wheelchair bound in her later life in Davenport.

Basic summary: A tenant farmer is on trial for killing a con man. The case is up in Lawrence County (abbreviated as L---- County in the original text). The accused, Dock Muckwrath, shot a man who "changed cards" on him. The general public figure since Dock lost all of his money in the world ($50) the killing was justified.

The jury ultimately lets Muckwarth off--not because they think he's not guilty, but because the foreman reveals how horrible convict camps are: "The doctor , who had the medical eye for com plexion, observed that Captain Baz was certainly very pale . “ My opinion, sir," said the captain , slowly,“ is that, in the present state of convicts in Arkansas, if you don't find the man not guilty you had better find him guilty enough to be hanged" (Thanet, p. 239). He goes on to explain that, "He told me, what I found was true, that the whole convict system is a money-making affair. They are all on the make. The board, commissioners, contractors, lessees, wardens, and guards, — they all just naturally squeeze the convict" (Thanet, p. 242). Captain Baz Lemew relates how he was in one himself, and how he blew the whistle on the abuses in the camp by passing a note to an inspector's sister in town. The horrible abusive Warden Moss turns out to be the scoundrel Muckwrath shot. So, the jury looks at the case as one where justice was meted out by the killing. Characters of note: Mr. Phillipson: The prosecutor. He asks "why a State so beautiful, so fertile, so attractive to every class of emigrants, is neglected" (Thanet, p. 226) and argues "It is because the old taint of blood and crime clings to our garments still" (Thanet, p. 226) and that they must convict to ensure that other people realize "that there is not in all this broad land a more peaceful, law-abiding section than ours, or a section with better enforced laws" (Thanet, p. 226). His argument is important as there is a Northerner in the audience, as Dr. Redden says to the others: "Phillipson was right; it discouraged immigration. He had seen Mr. Thornton (the Northerner) in court. They all knew he was fixing to build a canning factory. Was he likely to do that if they convinced him that any of his men could get mad and pop away at him with a gun, sure of getting off? It looked like they might lose their factory, may be their railroad, if they monkeyed with the verdict. Let them remember their oaths and the law; that was all he asked" (Thanet, p. 235). Dock Muckwrath is described as: "His face was of a type common in Arkansas among the renters, where the loosely hung mouth will often seem to contradict fine brows, straight noses, and shapely heads. One could see that he was wearing his poor best in clothes, namely, a new ill-fitting brown coat, blue trousers, rubber boots, and a white shirt with a brass collar-button but no necktie" (Thanet, p. 225). Captain Baz Lemew: The jury foreman. Dock is one of his renters (sharecropper/tenant farmer), and during deliberations, we learn that he was once Trusty, No. 49. He is now married to the inspector's sister--the same one he passed the note to in town. Dr. Redden: "desired a conviction ardently. His motives were the cleanest in the world. Of the new South himself, he believed in immigration, enterprise, and their natural promoters, law and order" (Thanet, p. 222). Thornton: Northerner in attendance at the trial who is planning on building a cannery in L----- County. His reaction to the verdict: "The Northerner, who was with Phillipson, laughed outright. 'They do seem pleased,' said he. 'See, Phillipson, there go the interesting family home together in one of the jurymen's wagon; Muckwrath is kissing the baby. Well, I confess I am glad he does n't have to go to your confounded penitentiary" (Thanet, p. 261). Notes on setting: The town used to be prosperous, but the railroad passed it by. Now, it is struggling, hence the importance of Thornton's cannery coming. The court is held in Barker's store, as the courthouse burned down some time ago. Interesting mix of business and law, of course. Given that so many of her Arkansas stories take place in spaces where boundaries are blurry and often circles of influence overlap (a judge sees a citizen in his home, a store becomes a court, people live on plantations--the very epitome of business and personal life being merged--people are property). Also, next door to the court/store is the local bar, Milligan's. Notes on dialect/language use: Trusty=Trustee in today's parlance. Thanet's Arkansas stories often deal with race, and characters often use the "N" word when referring to people of color. This is problematic, but to consider the characters' use of the term as a sign of Thanet/French's own racism is simplistic, in much the same way that banning The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for Huck's early use of the word is problematic. We cannot fully explain Alice French's views on race on the characters' use of the word. That's not to excuse the use of the word entirely, nor is it to say that Alice French did not have racist views herself. It is--much like the issue of her being an anti-suffrage activist in real life while also having her own wood working shop, her own photography studio, and being coupled with another woman and being out in her Boston Marriage on an old plantation in Arkansas--complicated.

Basic summary: Romance story; Rachel Meadowes and Archy (Captain Barris) are in love. Archy shows up to meet her father who disapproves of him because he drinks alcohol and they have opposing political views. After dinner Rachel tells Archy they can't marry. In his sadness, he leaves and decides to go to his rented room and write her a letter. The weather blows up a cyclone just as he sees the figure of Rachel ahead of him. He rushes to her and shields her body against a tree, begging her to hold on.

When the storm passes, Archy realizes it was not Rachel but her young stepmother who is the same shape and size as his beloved. He sees her home and when Meadowes sees she is safe, Archy admits he thought he was saving Rachel. His truthfulness wins the man over, and Meadowes finds him suitable to marry his daughter, even if he does drink a little. Discussion of temperance, Puritans, John Brown (Meadowes admires him so that he names one of his sons Ossawatomie). Even though both men admire Brown, Meadowes finds him faultless while Barris feels he made mistakes at Harper's Ferry (the death of innocent civilians). So, they weren't completely opposites on issues like abolition.

Basic summary: This story focuses on a feud between two neighbors, Luther Morrow and Dock Haskett. They had been feuding about who was the better shot, and when Morrow's dog, Jerusalem Jones, stole a ham from Haskett, he tried to shoot the dog and wound up hitting Morrow instead. Morrow shot Haskett in the shoulder as a result and the two are feuding. The two men decide to have a duel in the woods near where Haskett's wife is buried, but their children bring them back together.

The story opens with Minnie Haskett learning how to bake brown bread from Miss Dora. She's taken over the domestic duties at the small house since her mother died, and she loves her father so much she wants to cook well for him and her younger siblings. Even though Dock and Luther are fighting, Minnie and Doshy love each other and Minnie wants to teach Doshy how to make brown bread. Dock gives his consent, as he has no quarrel with any of the Morrows other than Luther. The two men are in the woods ready to shoot it out when they hear the two girls talking. They find a place in the brush to watch them and see them baking bread over a small fire. The two girls talk about how kind their fathers are as they work, and how much they love them, softening the men's hearts toward each other. Jerusalem Jones is playing with a small pig, and wild adult hogs come to the pig's defense. In the melee, the bread is disturbed but Morrow shoots the hogs and the day is saved--as is the "loaf of peace." Characters: Aunt Callie (seen in other stories), Miss Dora, Miss Carroll, Hasketts (Minnie and Dock), Doshy and Luther Morrow (Doshy is named after her mother, Mindosha), and, of course, Jerusalem Jones.

Basic summary: Characters: Mrs. Ponder, Mrs. Higgins, Miss Maine, Dosier, Chaney The story is set in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Dosier, a widow, works in the baths and has an invalid sister--Sist' Chaney. Dosier has a black silk gown and Chaney covets it. Mrs. Ponder says, ". . .she doesn't go out of the house once a year. If you please, ladies, she's plumb crazy for a black silk gown. Ever since Dosier got hers, she's been craving one" (Thanet, p. 142). Despite Mrs. Higgins objections that Dosier should not entertain Chaney's desire for the gown as they are poor and need the money for other things, the other women don't seem to feel the same. Dosier is not only highly praised among the three women in the baths; "Frequently she met acquaintances, black or white. They all greeted her with a degree of respect" (Thanet, p. 143). When Dosier arrives home, Chaney is crying and the doctors deliver the news that she can no longer leave the bed and is dying. Dosier realizes she can't go back to work and leave her sister unattended. Mrs. Ponder goes to visit, and she tells Higgins and Maine all about it. Mrs. Higgins thinks Chaney should be "glad to go" (Thanet, p. 151). Miss Maine suggests that Chaney should want to be with her dead husband, to which Mrs. Ponder reponds "I don't guess he counts much. He was a trifling no-'count n____, who wanted to wear his Sunday clothes every day, and sit in the store-doors and ogle the yellow girls. I reckon he wasn't any too kind to her, either, ayfter she got too sick to earn money for him to spend" (Thanet, p. 152). The story is remarkable largely for what it says about race relations. On page 143, there's a description of main street: At that hour of the day the Hot Springs main street is a picturesque scene, a kaleidoscope of shifting figures, all tints of skin, all social ranks; uncouth countrymen on cotton wagons; negroes in cars drawn by oxen or skelton mules with rope harness; pigs lifting their protesting noses out of some carts, fowls squawking in others; a dead deer flug over a horseman's saddle; modish-looking men and women walking; shining horses curveting before handsome carriages; cripples on crutches; deformed creatures hugging the sunny side of the street before the bathhouses; pale ghosts of human beings in wheeled chairs,---so the endless procession of wealth or poverty or disease or hope oscillates along the winding street between the mountains." Even on her deathbed, Chaney says she'd rather have her desired black silk than go to heaven (pp. 148-9). After Mrs. Ponder suggests Dosier tell Chaney about the fine funeral she will provide for her sister, she does, inviting Miss Betty (Ponder) to go see Chaney. Yes, honey, dat so; but ef you didn't have a good time, you shall have de bigges' an' de nices' burryin' of ary cullud pusson in Hot Springs." (Thanet, p. 155) The story ends with a description of the funeral; Chaney is comforted enough by the pledge of the black silk that she dies in peace. We see Ponder and Maine discuss how peaceful and beautiful the funeral was. When Miss Maine mentions it's a shame Chaney "couldn't see her own funeral" (Thanet, p. 159) Ponder responds with "Well, I don't know; perhaps she did" (Thanety, p. 159). Take aways: The story sets up several instances where stereotypes are chipped away at. Not only do we see how intimate the interactions are between white clients and black bath attendants in the story, but we also see strength in Chaney versus Mrs. Higgins. Mrs. Higgins says she wants to die when her hands are in an arthritic flare, which is why she says--even before Chaney is clearly on her deathbed--that she doesn't know how Chaney stands living. It's a nice touch, then, that Dosier shares gifts Mrs. Higgins has given her with Chaney for the funeral, since Higgins gripes about how "silly" Chaney is for coveting a black silk gown when she obviously has more important things to worry about. The love the sisters share and how Dosier would do anything for her sister is the obvious focus here. The doctors have a brief conversation about Dosier's grief--one mentioning that it seems odd to him that Dosier doesn't seem relieved to soon be on her own after taking care of her sister for so long: "'Bracing up,' muttered the youngest man. 'She feels bad. Queer, too; the woman's always been a burden to her.'" Dr. Le Verneau, irritated, responds, "'That's all you know about it, . . . Don't you suppose she's fond of her kin? That poor soul there has lived with Dosier for twenty years." (Thanet, pp. 146-7). Ponder and Le Verneau seem to be the most sympathetic and understanding of Dosier and Chaney, seeing them as humans with the same level of emotional capability as themselves. Side note: A lot of talk about chewing gum as a habit at the beginning of the story. Also, a bit of discussion of how Dosier's late husband shot a gangster--a good bit of local color writing about Hot Springs. Late in the story, we find Mrs. Ponder is hooked: " Gum had become a sort of intellectual motor to Mrs. Ponder, who never felt her mind really working without a simultaneous action of her jaws" (Thanet, p. 153).

Basic summary: This is the story of Atherton--both the Western town and the man it was named for. Katy and Tom Ransome, young lovers who married despite family objections, are lured to Atherton for Tom to become the editor of the paper, The Citizen. Once there, they meet Atherton--the first mayor of the town, his wife (the widow Bainbridge and her daughter), and Renee, the Louisiana native who also followed the Westward expansion.

Initially, Katy is put off by Atherton, but the more she learns about him, the more she likes him. Over and over again he puts himself at risk to help others--first, it is the man who confronts him for putting him out of business. We learn later that he hired the man at a salary higher than he ever made when running the business, though, and that the business failing was a blessing. After his wife and children died of Cholera, he married the widow Bainbridge who was destitute after her own husband died. Her daughter Rose tried to stab Atherton with a penknife on their wedding day, but he was later her friend. Atherton has gone so far as to guarantee currency, and when the bank goes bust, he is elected out of office. His wife dies in a carriage accident, and he winds up having a fit of apoplexy. Katy and Tom move, and when they return ten years later, the town has been renamed and it is only by finding the monument Atherton had built for his first wife and three lost children that they realize they've found his grave, as well. Items of note:

Notes:

I was excited to begin Otto the Knight and Other Trans Mississippi Stories in part because of the regional focus. A few of these stories carry over characters from stories published in Knitters in the Sun. Michael B. and Carol W. Dougan's 1980 collection By the Cypress Swamp: The Arkansas Stories of Octave Thanet brings many of those stories together, although the title story "Otto the Knight" is not in that collection. Given the very light emphasis on the setting here, the omission of the story isn't completely surprising. McMichael also only mentions the story itself on page 125, indicating that it was chosen as the title for the collection solely based on the fact it was the first story. The omission is interesting, given that Lum Shinault definitely lives on the Black River in "Whitsun Harp, Regulator" and because there is the connection to getting lost in the swamp. Marty Ann searching for Boo gets lost, just as Ma' Bowlin got lost in the earlier story. Basic Summary:

Basic Plot Summary: Part I: Polly Ann Shinault, wife of Lum, is out fixing the Clover Bend ferry-boat when she sees Whitsun Harp in the boat with her neighbor Boas. Harp has come by because he's heard Lum and Polly are missing a mule, and Polly acknowledges that, saying that Lum is off looking for it, but they assume it has been stolen. He proceeds to tell her his story of becoming a regulator, and how it seems like a calling from God. It's pretty clear Harp was sweet on Polly but Lum beat him to her. Harp mentions that as kids they played together and he told her everything then, which is why he felt the need to personally tell her why he had become a regulator.When he leaves, Boas tells Polly that Harp already warned Lum to shape up and to stop partying. He emphasizes the importance of Lum doing so by telling her different stories of Harp "giving a lickin'" to various people. Lum comes home for supper and when Polly tells him Harp finds him "trifflin'" Lum indicates Harp had better mind his own business. We learn that Lum helps his wife with household chores, having helped his mother because his father was 'triflin.'" We also learn that "he had married Polly Ann out of compassion" (Thanet, p. 316) when her father died. He reasoned that "Nary un waiti' on 'er neether, 'less hit ar' Whitsun Harp. Ef he don' marry her, I reckon Ihed orter. 'Tain't no mo'n neighborly.' //Whitsun making no sign, he carried out his intention" (Thanet, p. 316). In a conversation with Boas, Lum reveals the truth about his interactions with Savannah Lady. They are merely trying to make the man she loves jealous, and Lum thinks there's no harm in it. The trick works, and Morrow proposes to Savannah. Unfortunately, Lum, Whitsun, Polly, and Savannah all converge in the dry bottoms of the swamp and Harp mistakes Lum helping Savannah by giving her whiskey when she is ill to be some romantic tryst. He breaks of a switch and beats Lum. Polly sees it all and chides Lum for not standing up for himself, but she assures him she'll cook him a good dinner. Lum is ashamed and cries because he thinks Polly doesn't love him, and he's sure this was the final straw. Part II: Lum doesn't come home for dinner, despite Polly waiting. She finds a note that indicates he won't be back (Thanet, p. 328). He has taken the gun and plans to kill Whitsun Harp. "He had been beaten before his wife, his wife who valued strength and bravery beyond everything. And Whitsun, whom she praised because he was so strong and brave had beaten him" (Thanet, p. 328). He knows this is a high priority for Polly as her father, Old Man Gooden, shot a man for spitting in his face. According to Polly, "Paw hed ter shoot him" (Thanet, p. 329). Lum assumes Polly pines after Harp, and he decides that if Harp kills him, Polly won't take up with him. On the other hand, if he kills Harp, Polly will never forgive him, either. So, his plan is to "go off on the cotton-boat afore sundown. All through this wide worl' I'll wander, my lone" (Thanet, p.329). Lum (short for Columbus) crosses paths with Boas,who is dying. Boas tells Lum he's come out to warn Harp that some other men are coming to kill him. Boas killed another man a few years back, and ever since he's been haunted by it. He fears going to hell, and he hopes that by warning Harp, God will give him mercy. Unfortunately, he's too weak to go all the way across the swamp and he begs Lum to do it for him. Lum does, but he tells Harp that as soon as Boas dies, he will kill Harp. Harp, upon hearing the truth about Savannah, swears he'll make it up to Lum and Polly, but Lum says there's no way he can. It takes three weeks for Boas to die and Lum acts weird, taking to the woods mostly. Polly worries about him and follows him, but she's not sure what to do and just fears he's gone mad. When Boas dies, Lum joins Harp at the grave and tells him he's still going to kill him and where to meet after the funeral. Harp asks Lum to meet him at the plantation store first, and he does. Harp makes things right by admitting to being wrong and apologizes. He and Lum shake hands, and Lum decides to go squirrel hunting. Meanwhile, Polly notices Lum's boat is gone and she follows him to Clover Bend (using Boas' boat). She hears a single shot and runs towards it, finding Harp dead on the ground, a smile on his face. Lum is nearby, but he tells her the story of how Harp made things right and that it wasn't he who shot him. He tells Polly he'll leave her to her goodbyes, and she realizes he thinks she loves Harp. It turns out she never loved anyone but Lum, and the story ends with them embracing, Harp's dead, smiling body still on the ground. Perhaps you will excuse my mentioning that Whitsun Harp is almost entirely a true story. Harp lived and died as I have tried to picture and Boas was haunted as I have described and (although not in Clover Bend) I know of a Lum saved as Shinault was. This is no excuse for me if I haven't made the story real; I only mention it to show that I have no such notions as you impute to me; but am as uncompromising a realist as lives. I have tried not to idealize my friends of the Cypress Swamp, one atom . . .

Basic Plot: Mrs. Legare has a devoted servant (former slave) named Venus. Johnny (Union soldier) meets Legare and befriends Venus at the start of the story and spends lots of time with her in the gardens and the kitchen before returning North. When he returns after the war, he finds that the property has been taken by Baldwin, who we later learn, from Mrs. LeGare: He was an overseer on my uncle's plantation , and was sent away for cheating. He went into the Yankee army afterward as a sutler, but he had to leave because he would get provisions for the people here from the commissary and then sell the provisions. (Thanet, p. 286) Baldwin refuses to let Venus pay the property tax, as she is not the owner (LeGare is away when the war taxes are due), and he buys the property out of spite. Venus puts a curse on him (only half of one, though, as her mother never taught her any full curses). Despite the fact he isn't living on the property, Baldwin refuses all offers to buy the property back (from LeGare, Johnny, Venus), and eventually gets Yellow Fever. Despite his orders for LeGare to leave the property, she determines she will go nurse his family back to health. Venus goes in her place. She, of course, contracts the disease and dies, proclaiming it is her punishment for the "half a curse." Baldwin shows up on her funeral day to evict LeGare, but his heart is softened when she tells him it was Venus who nursed his family back from the brink of death. He gives the house back (no payment). McMichael does a great job of summarizing some of the issues here: The story followed the romanticized tradition of post-bellum southern fiction with its mansion,its southern belle, and its Negro mammy, a loyal and noble illiterate providing wisdom and salvation for her betters. The resolution brought by the union of the Yankee officer (Johnathan) and the southern [widowed] maiden, reuniting the North and South, was an equally overworked convention. (p. 102)

Basic Plot: Bud Quinn and his wife Sukey live in Clover Bend. Bud was almost hanged on the day Ma' Bowlin' was born, as William Ruffner thought he had murdered his boy, Zed. Zed disappeared eight years ago, and rumor was that Bud killed him and fed him to the hogs. Sukey saved him that day by reasoning with the men (hooded klansmen, it appears) that Bud didn't have a mark on him, and he would have if he'd killed Zed who was larger and stronger than he was. The story opens with Mrs. Brand, a widow from Georgia, visiting Sukey as she finishes a new dress for Ma' Bowlin'. Sukey makes sure to instruct her daughter not to get the gown dirty, and the girl promises before setting out to the plantation store to meet her father to show him her new dress. Bud arrives home alone, and a search party begins looking for the girl. Bud was ashamed of Ma' Bowlin's feeble-mindedness and never cared for the child; upon seeing how upset Sukey is, though, he realizes he, too, loves Ma' Bowlin.' He goes searching for her, and he and Ruffner find her--and Zed. The gown is clean and the family is reunited. She was a baby ; a girl, when he wanted a boy; she was a toddling little thing who wouldn't learn to talk, but used queer sounds of her own for a language; he had a notion that it was this which first gave him his repugnance to the child . She was a girl whose feeble mind was a judgment ; then he slowly grew to hate her . He didn't know whether he hated her now or not ; he only knew that if Sukey wanted her so bad, she must have her. (Thanet, p. 252) Interestingly, when she appears on Zed's boat, she's cured: Her face looked like an angel's to him in its cloud of shining hair; her eyes sparkled, her cheeks were red, but there was something else which in the intense emo tion of the moment Bud dimly perceived — the familiar dazed look was gone. . How the blur came over that innocent soul , why it went , are alike mysteries. (Thanet, p. 264)

Basic Plot: The Berkelys are on a steamboat and land on the shore of Lake Pepin, where they meet up with a hermit. The man was once a church going man, but he turned away from faith and toward philosophy. His wife and son died of diptheria and he adopted his daughter out to relatives. Ethel Berkely convinces the hermit that what matters is "good works." Years later, she finds out he died of yellow fever in Mississippi where he had gone to volunteer to help those who were ill.

Basic Plot:

This story covers an interesting relationship between and a strange Countess an old childhood friend who has recently been widowed. The countess has taken a job to help support the window and the focus of the story is on the Bailey family. The husband and the Bailey family is a communist head because of his principles has been out of work. His wife comes to the two women and asks for assistance. Bailey refuses to give up his affiliations with the union and the Countess refuses to hire him on without the promise that he will not unionize and strike. Within this story the countess makes two offers to employ Bailey, and she’s turned down both times. The Bailey family moves to Chicago where the countess later has to journey in order to settle the conditions of her husband’s will when he dies. She arrives on the day of The Railroad Strike of 1877 in Chicago and sees Mrs. Bailey shortly before she is trampled and shot during the riots. Coincidentally, she winds up in the same room with Mr. Bailey as they bring in the body of his dead wife. Bailey accuses the countess of murdering his wife, and she denies the accusation, reminding him that she offered him a job twice. The story ends with neither agreeing. This story is yet another example within this collection of Thanet bringing together opposing social and economic status people into a stalemate. The story is remarkable mainly for this, but also for the depiction of the relationship between the countess and her living companion.

Basic Plot Summary: Harold Durham has just been dumped by Lilian "Lily" Maines because she couldn't "give up my friends and my convictions for you" (p. 134). Lily is part of the suffrage movement, and we find that Harold attempted to attend a meeting (p. 110) but found the women coarse. He is surprised to learn Lily is pro-suffrage, as her hair is not cut short (p. 142). Traveling from Chicago to Xerxes to repair his father's tenement buildings, Harold meets Father Quinnailion and befriends him, after struggling a lot with his image of what Catholics are like versus the example Father Q. shows him. After he realizes that Catholics are not horrible heretics who pray to Mary and other saints, he realizes, too, that he was wrong to want to force Lily to "convert" and give up her principles. I been unjust and cruel to you? By Jove, I'm not only a bigot but a snob; I needed Father Quinnailon to take the worldliness out of me . What right had I to ask Lily to give up her principles? It was just the same conceited stuff as my wanting those poor creatures in the church to give up the religion which helps them to bear their hard lives! (p. 171) McMichael, interestingly, doesn't discuss or analyze this story. This is significant given his overall argument that Thanet was anti-suffrage for women. This story seems to present things in a more complex light--Harold and Lily reconcile at the end and true love wins, despite the differences in principles.

|

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed