|

"The Ogre of Ha Ha Bay"

A newly married and honeymooning couple, Maurice and Susan, meet up with the Ogre and his nephew, Isadore Clovis, who is the carriage cab-man of sorts. The Ogre, Tremblay (p. 5), took a vow (p. 6) 25 years prior to never enter his new home until he takes a maiden of 20. Tremblay was engaged to the now widowed Madame Guion many years ago (p. 6), but she rejected him and married for love, rather than money, which we discover later. Tremblay arranges to marry her daughter, Melanie (p. 12). Melanie goes along with the plan, in part because Tremblay has always been kind to her and her mother. Melanie and Isadore are in love, but Tremblay has enough money to pay for her mother’s eye surgery, without which she will go blind. The interesting points of the story include the point of view (that the narrator is male and Thanet takes pleasure in describing Susan as the object of marital affection in the opening paragraphs and that Guion’s story of her marriage (p. 21) focuses on the discussion of domestic violence and hardship for women: It was twenty-five years ago, and M. Tremblay would marry me, but I was a fool, I: my heart was set on a young man of this parish, tall, strong, handsome. I quarreled with all my relations, I married him, M’sieu’. Within a month of our wedding day he broke my arm, twisting it to hurt me. He was the devil. Twice, but for his brother, he would have killed me. (Madame Guion to Maurice, p. 19) Domestic violence and marriage are both themes I plan to watch out for, as A Slave to Duty is a collection largely focused on those themes. “Love, it is pleasant, but marriage, that is another pair of sleeves” (21). The narrator reflects: But I thought that I understood the situation better. I believed Madame Guion told us the truth: she was only seeking her daughter’s happiness. She had an intense but narrow nature, and her life of toil, hard and busy thought it was, being also lonely and quiet, rather helped than hindered brooding over her sorrows. Her mind was of the true peasant type, the ideas came slowly and were tenacious of grip. Love had been ruin to her. It meant heartbreak, bodily anguish, the torture of impotent anger, and the bitterest humiliation.(Maurice, p. 23) The abusive relationships are off-set by the love of Susan and Maurice, the happy American couple (the story is set in Canada) who work at matchmaking and feud mending. In the end, Isadore sets fire to his uncle’s new house, figuring that if he has no new house, he has no reason to marry. In the end, Tremblay comes to his senses, embraces Melanie as his niece (after testing her to make sure she will still marry him) and pays for the Widow’s eye cure. In the end, the Widow is still opposed to the marriage between Isadore and Melanie, but they hope she’ll come around.

0 Comments

Gillette's "article takes up [Koppelman's] invitation and joins recent reappraisals of French's work by seeking to make more visible her contributions to gay and lesbian writing" (p. 141). Koppelman's inclusion of "My Lorelei: A Heidelberg Romance" in her 1994 collection Two Friends and Other Nineteenth-Century Lesbian Stories by American Women Writers was the springboard for Gillette's essay which covers "My Lorelei," "The Stout Miss Hopkins' Bicycle," and "The Rented House" as stories that challenge heteronormativity: a shared kiss between women in "My Lorelei," a challenge of body norms in "The Stout Miss Hopkins' Bicycle," and "heteronormativity as a form of body-snatching" (p. 140) in "The Rented House." What interests me about this recent article is that Gillette gives me hope that earlier criticism of Thanet (what little there is) was short-sighted: "But while French did indeed hold and espouse many conservative views, this narrow characterization of her life and writing omits too much. . . . Significantly, none of these readings match what we might expect a 'conservative' writer to write about. That the names Alice French and Jane Crawford have also begun to appear in gay and lesbian histories and chronologies and anthologies of gay and lesbian literature likewise suggests more to her writing than previously thought" (p. 141). Alice and Jane spent a lot of time together in their teens and early twenties, according to Gillette. In 1872, Jane married Joseph Crawford. Gillette mentions that McMichael assumed she was widowed, "the 1880 census, which found Jenny Crawford living at home with her parents. . .identifies her marital status with a D for divorced" (p. 143). By 1882, Alice and Jane had "rekindled" their relationship. While McMichael dismissed/ignored the romantic nature of Alice and Jane's relationship, Gillette uses Faderman's earlier (1981) discussion of Boston Marriages and examples from letters to show that McMichael's characterization of French's emotional letters as being "exaggerated" rather than romantic that he likely didn't have a full understanding of intimate female relationships.

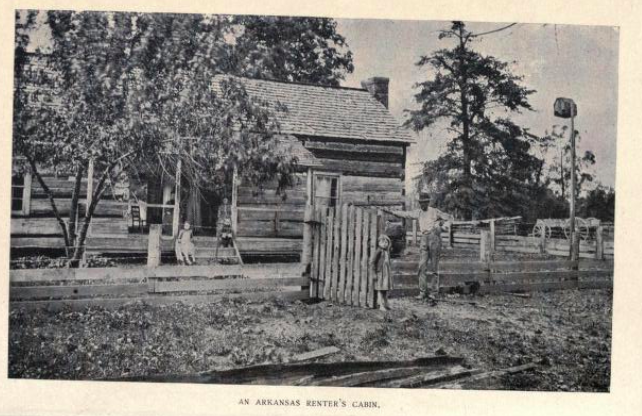

That's all I have to share today, but the news that Jane may have been divorced rather than widowed was a revelation. Gillette, Meg. "Keeping Queer Company in the Short Fiction of Alice French." American Literary Realism. Winter 2021: 53(2). pp. 138-158 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/amerlitereal.53.2.0138 My entertainment this morning is Octave Thanet's An Adventure in Photography, published in 1893. This book is for purchase, and I can snag a signed first edition for around $125 (granted, the description indicates it needs to be rebound) or an unsigned for $40. The book opens with a lovely indication of Octave and Jane's relationship, and the narrative parts of the book are a sweet glimpse into their home life and common interests, complete with dialogue. THPlenty of pictures here of Thanford and surrounding areas in Clover Bend, including this one, which strikes me on a personal level. My paternal grandfather was a tenant farmer in Arkansas. I have many reasons for my starts and stops on this project; understandably when it was necessary for me to work for other people during Dani's medical school and residency, I simply didn't have the time or emotional energy to work on it consistently.

However, I'm also very aware that one factor contributing to the seventeen year gap between declaring I would pursue the project and yesterday when I finally sat down and started is that Octave Thanet is a contradictory character and there's a ton of things about her that are going to be uncomfortable. The very fact that she owned a plantation in Arkansas is prickly for me, as is her fairly well-documented anti-suffrage position. But, that's the goal of this journey--to figure her out. Her one published biography is older than I am, after all, and perhaps a fellow lesbian and Arkansan by choice can add to our understanding of her life and how she lived it. The first published story by Alice French was published in the Davenport Gazette in February 1871 under the pseudonym Frances Essex. In the only currently existing biography of French, George McMichael's 1965 Journey to Obscurity: The Life of Octave Thanet, McMichael notes "The manuscript remained among her papers after her death. Her mother had written on it 'This is Alice's first published story.'" (note on page 43). I also send that little story I read so long ago to you. . .Do you remember it? Mr. Sanders wanted something for this Saturday's Gazette, so I finished up that. It is very stupid, I know, but it was written for the popular taste, which is also stupid. While the manuscript is among French's papers, her statements about that story clearly indicate why I can't find a digital copy today. McMichael suggests that the paper likely published it because the editor "was a friend of Alice's father and knew the virtues of local authors" (McMichael, 43).

You can check out the biography, which is a published version of McMichael's dissertation, at the Internet Archive if you have an account. My first encounter with Octave Thanet/Alice French was the four paragraphs in Lilian Faderman's classic work Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women From the Renaissance to the Present: In America the author Alice French, who wrote under the name Octave Thanet, and Jane Crawford, her companion of almost half a century, also had a relationship in which the energies of both went into the career of one. Octave, who for thirty years was among the highest paid writers in the United States, also came to literature as a business--and her success in it was due at least in part to the nurturing support that Jane gave her. Thanet's success and her relationship with Crawford would be enough to gain my interest; after all, my dissertation focuses on three-named female writers who may or may not have been lesbians who were highly successful and are all but forgotten: Mary Wilkins Freeman, Sarah Orne Jewett, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Sure, we all read a single short story by these women in our American Literature surveys, but they were as successful or more so than their contemporary male writers like Twain, Hawthorne, and Melville. Add to the mix here that Thanet and Crawford owned a property in Clover Bend, Arkansas that they named "Thanford" and that Alice/Octave was anti-suffrage, worked in her woodshop, was a skilled photographer, and, according to Faderman, "seemed to view humanity as having three sexes--men, women, and Octave Thanet" how could I not go on a voyage to figure Octave Thanet out?

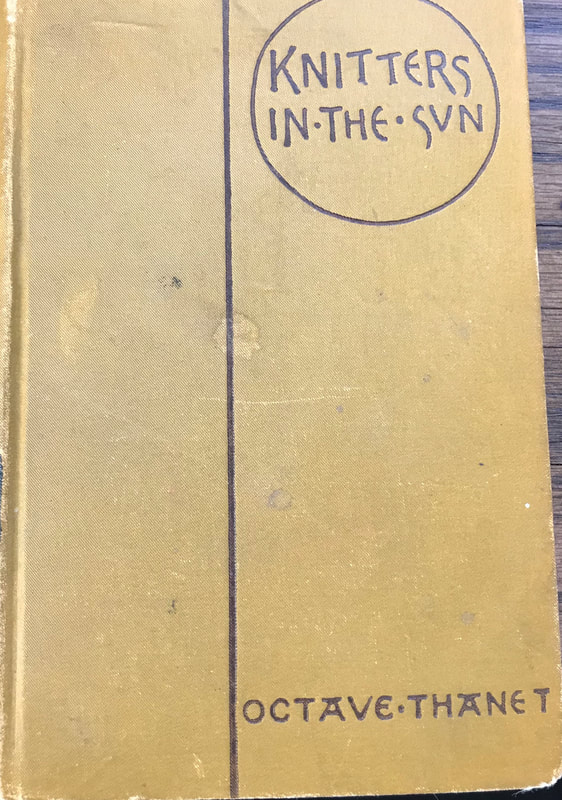

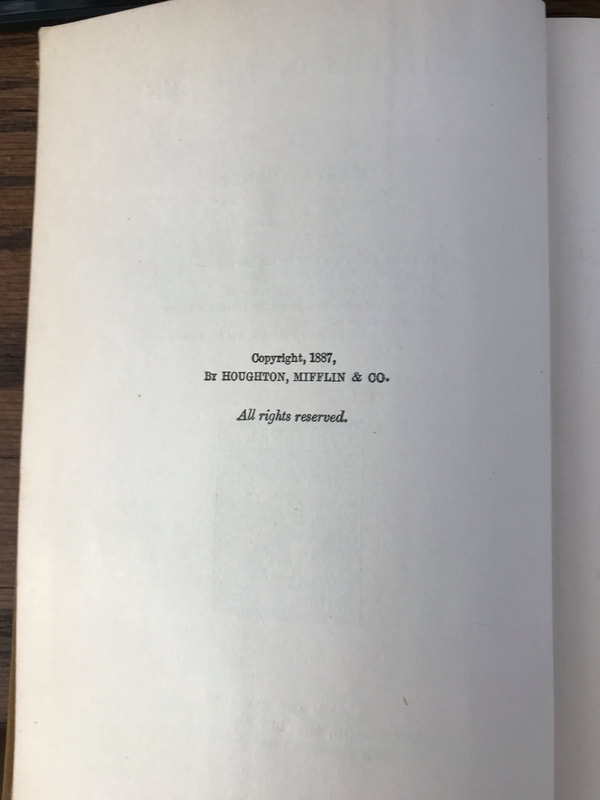

And, on the morning I decided to start, what do I see but an article "Keeping Queer Company in the Short Fiction of Alice French" by Meg Gillette in the most recent issue of American Literary Realism. So, old Alice is getting other folks' attention too. I'll be starting my primary text reading with Knitters in the Sun, her collection from 1887. While I have the copy pictured below, I'll be using the scanned text to save my first edition. |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed