|

0 Comments

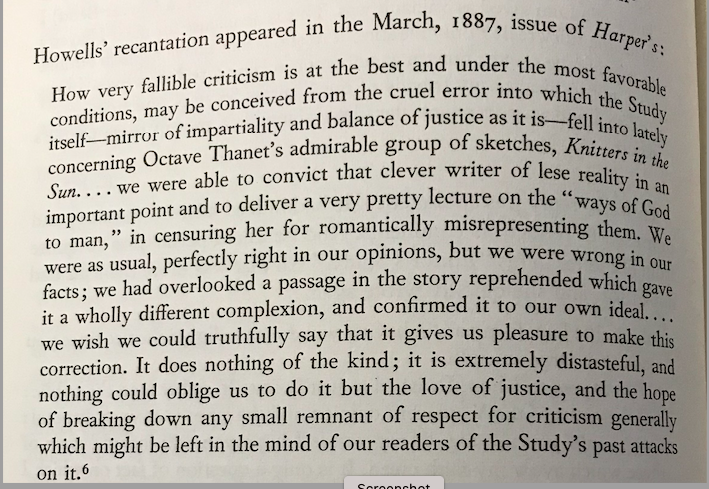

Basic Plot Summary: Part I: Polly Ann Shinault, wife of Lum, is out fixing the Clover Bend ferry-boat when she sees Whitsun Harp in the boat with her neighbor Boas. Harp has come by because he's heard Lum and Polly are missing a mule, and Polly acknowledges that, saying that Lum is off looking for it, but they assume it has been stolen. He proceeds to tell her his story of becoming a regulator, and how it seems like a calling from God. It's pretty clear Harp was sweet on Polly but Lum beat him to her. Harp mentions that as kids they played together and he told her everything then, which is why he felt the need to personally tell her why he had become a regulator.When he leaves, Boas tells Polly that Harp already warned Lum to shape up and to stop partying. He emphasizes the importance of Lum doing so by telling her different stories of Harp "giving a lickin'" to various people. Lum comes home for supper and when Polly tells him Harp finds him "trifflin'" Lum indicates Harp had better mind his own business. We learn that Lum helps his wife with household chores, having helped his mother because his father was 'triflin.'" We also learn that "he had married Polly Ann out of compassion" (Thanet, p. 316) when her father died. He reasoned that "Nary un waiti' on 'er neether, 'less hit ar' Whitsun Harp. Ef he don' marry her, I reckon Ihed orter. 'Tain't no mo'n neighborly.' //Whitsun making no sign, he carried out his intention" (Thanet, p. 316). In a conversation with Boas, Lum reveals the truth about his interactions with Savannah Lady. They are merely trying to make the man she loves jealous, and Lum thinks there's no harm in it. The trick works, and Morrow proposes to Savannah. Unfortunately, Lum, Whitsun, Polly, and Savannah all converge in the dry bottoms of the swamp and Harp mistakes Lum helping Savannah by giving her whiskey when she is ill to be some romantic tryst. He breaks of a switch and beats Lum. Polly sees it all and chides Lum for not standing up for himself, but she assures him she'll cook him a good dinner. Lum is ashamed and cries because he thinks Polly doesn't love him, and he's sure this was the final straw. Part II: Lum doesn't come home for dinner, despite Polly waiting. She finds a note that indicates he won't be back (Thanet, p. 328). He has taken the gun and plans to kill Whitsun Harp. "He had been beaten before his wife, his wife who valued strength and bravery beyond everything. And Whitsun, whom she praised because he was so strong and brave had beaten him" (Thanet, p. 328). He knows this is a high priority for Polly as her father, Old Man Gooden, shot a man for spitting in his face. According to Polly, "Paw hed ter shoot him" (Thanet, p. 329). Lum assumes Polly pines after Harp, and he decides that if Harp kills him, Polly won't take up with him. On the other hand, if he kills Harp, Polly will never forgive him, either. So, his plan is to "go off on the cotton-boat afore sundown. All through this wide worl' I'll wander, my lone" (Thanet, p.329). Lum (short for Columbus) crosses paths with Boas,who is dying. Boas tells Lum he's come out to warn Harp that some other men are coming to kill him. Boas killed another man a few years back, and ever since he's been haunted by it. He fears going to hell, and he hopes that by warning Harp, God will give him mercy. Unfortunately, he's too weak to go all the way across the swamp and he begs Lum to do it for him. Lum does, but he tells Harp that as soon as Boas dies, he will kill Harp. Harp, upon hearing the truth about Savannah, swears he'll make it up to Lum and Polly, but Lum says there's no way he can. It takes three weeks for Boas to die and Lum acts weird, taking to the woods mostly. Polly worries about him and follows him, but she's not sure what to do and just fears he's gone mad. When Boas dies, Lum joins Harp at the grave and tells him he's still going to kill him and where to meet after the funeral. Harp asks Lum to meet him at the plantation store first, and he does. Harp makes things right by admitting to being wrong and apologizes. He and Lum shake hands, and Lum decides to go squirrel hunting. Meanwhile, Polly notices Lum's boat is gone and she follows him to Clover Bend (using Boas' boat). She hears a single shot and runs towards it, finding Harp dead on the ground, a smile on his face. Lum is nearby, but he tells her the story of how Harp made things right and that it wasn't he who shot him. He tells Polly he'll leave her to her goodbyes, and she realizes he thinks she loves Harp. It turns out she never loved anyone but Lum, and the story ends with them embracing, Harp's dead, smiling body still on the ground. Perhaps you will excuse my mentioning that Whitsun Harp is almost entirely a true story. Harp lived and died as I have tried to picture and Boas was haunted as I have described and (although not in Clover Bend) I know of a Lum saved as Shinault was. This is no excuse for me if I haven't made the story real; I only mention it to show that I have no such notions as you impute to me; but am as uncompromising a realist as lives. I have tried not to idealize my friends of the Cypress Swamp, one atom . . .

Basic Plot: Mrs. Legare has a devoted servant (former slave) named Venus. Johnny (Union soldier) meets Legare and befriends Venus at the start of the story and spends lots of time with her in the gardens and the kitchen before returning North. When he returns after the war, he finds that the property has been taken by Baldwin, who we later learn, from Mrs. LeGare: He was an overseer on my uncle's plantation , and was sent away for cheating. He went into the Yankee army afterward as a sutler, but he had to leave because he would get provisions for the people here from the commissary and then sell the provisions. (Thanet, p. 286) Baldwin refuses to let Venus pay the property tax, as she is not the owner (LeGare is away when the war taxes are due), and he buys the property out of spite. Venus puts a curse on him (only half of one, though, as her mother never taught her any full curses). Despite the fact he isn't living on the property, Baldwin refuses all offers to buy the property back (from LeGare, Johnny, Venus), and eventually gets Yellow Fever. Despite his orders for LeGare to leave the property, she determines she will go nurse his family back to health. Venus goes in her place. She, of course, contracts the disease and dies, proclaiming it is her punishment for the "half a curse." Baldwin shows up on her funeral day to evict LeGare, but his heart is softened when she tells him it was Venus who nursed his family back from the brink of death. He gives the house back (no payment). McMichael does a great job of summarizing some of the issues here: The story followed the romanticized tradition of post-bellum southern fiction with its mansion,its southern belle, and its Negro mammy, a loyal and noble illiterate providing wisdom and salvation for her betters. The resolution brought by the union of the Yankee officer (Johnathan) and the southern [widowed] maiden, reuniting the North and South, was an equally overworked convention. (p. 102)

Basic Plot: Bud Quinn and his wife Sukey live in Clover Bend. Bud was almost hanged on the day Ma' Bowlin' was born, as William Ruffner thought he had murdered his boy, Zed. Zed disappeared eight years ago, and rumor was that Bud killed him and fed him to the hogs. Sukey saved him that day by reasoning with the men (hooded klansmen, it appears) that Bud didn't have a mark on him, and he would have if he'd killed Zed who was larger and stronger than he was. The story opens with Mrs. Brand, a widow from Georgia, visiting Sukey as she finishes a new dress for Ma' Bowlin'. Sukey makes sure to instruct her daughter not to get the gown dirty, and the girl promises before setting out to the plantation store to meet her father to show him her new dress. Bud arrives home alone, and a search party begins looking for the girl. Bud was ashamed of Ma' Bowlin's feeble-mindedness and never cared for the child; upon seeing how upset Sukey is, though, he realizes he, too, loves Ma' Bowlin.' He goes searching for her, and he and Ruffner find her--and Zed. The gown is clean and the family is reunited. She was a baby ; a girl, when he wanted a boy; she was a toddling little thing who wouldn't learn to talk, but used queer sounds of her own for a language; he had a notion that it was this which first gave him his repugnance to the child . She was a girl whose feeble mind was a judgment ; then he slowly grew to hate her . He didn't know whether he hated her now or not ; he only knew that if Sukey wanted her so bad, she must have her. (Thanet, p. 252) Interestingly, when she appears on Zed's boat, she's cured: Her face looked like an angel's to him in its cloud of shining hair; her eyes sparkled, her cheeks were red, but there was something else which in the intense emo tion of the moment Bud dimly perceived — the familiar dazed look was gone. . How the blur came over that innocent soul , why it went , are alike mysteries. (Thanet, p. 264)

Basic Plot: The Berkelys are on a steamboat and land on the shore of Lake Pepin, where they meet up with a hermit. The man was once a church going man, but he turned away from faith and toward philosophy. His wife and son died of diptheria and he adopted his daughter out to relatives. Ethel Berkely convinces the hermit that what matters is "good works." Years later, she finds out he died of yellow fever in Mississippi where he had gone to volunteer to help those who were ill.

Basic Plot:

This story covers an interesting relationship between and a strange Countess an old childhood friend who has recently been widowed. The countess has taken a job to help support the window and the focus of the story is on the Bailey family. The husband and the Bailey family is a communist head because of his principles has been out of work. His wife comes to the two women and asks for assistance. Bailey refuses to give up his affiliations with the union and the Countess refuses to hire him on without the promise that he will not unionize and strike. Within this story the countess makes two offers to employ Bailey, and she’s turned down both times. The Bailey family moves to Chicago where the countess later has to journey in order to settle the conditions of her husband’s will when he dies. She arrives on the day of The Railroad Strike of 1877 in Chicago and sees Mrs. Bailey shortly before she is trampled and shot during the riots. Coincidentally, she winds up in the same room with Mr. Bailey as they bring in the body of his dead wife. Bailey accuses the countess of murdering his wife, and she denies the accusation, reminding him that she offered him a job twice. The story ends with neither agreeing. This story is yet another example within this collection of Thanet bringing together opposing social and economic status people into a stalemate. The story is remarkable mainly for this, but also for the depiction of the relationship between the countess and her living companion.

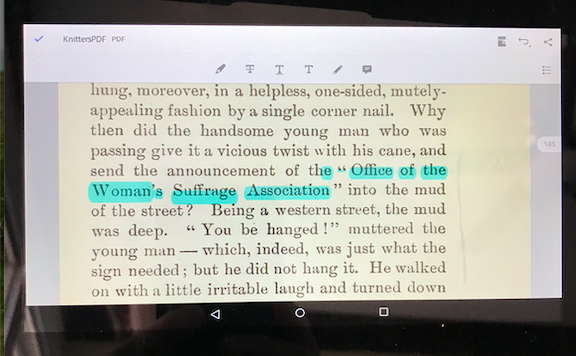

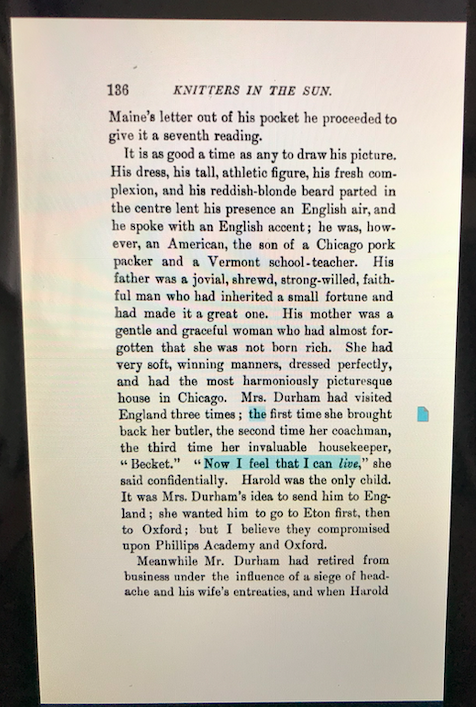

Basic Plot Summary: Harold Durham has just been dumped by Lilian "Lily" Maines because she couldn't "give up my friends and my convictions for you" (p. 134). Lily is part of the suffrage movement, and we find that Harold attempted to attend a meeting (p. 110) but found the women coarse. He is surprised to learn Lily is pro-suffrage, as her hair is not cut short (p. 142). Traveling from Chicago to Xerxes to repair his father's tenement buildings, Harold meets Father Quinnailion and befriends him, after struggling a lot with his image of what Catholics are like versus the example Father Q. shows him. After he realizes that Catholics are not horrible heretics who pray to Mary and other saints, he realizes, too, that he was wrong to want to force Lily to "convert" and give up her principles. I been unjust and cruel to you? By Jove, I'm not only a bigot but a snob; I needed Father Quinnailon to take the worldliness out of me . What right had I to ask Lily to give up her principles? It was just the same conceited stuff as my wanting those poor creatures in the church to give up the religion which helps them to bear their hard lives! (p. 171) McMichael, interestingly, doesn't discuss or analyze this story. This is significant given his overall argument that Thanet was anti-suffrage for women. This story seems to present things in a more complex light--Harold and Lily reconcile at the end and true love wins, despite the differences in principles.

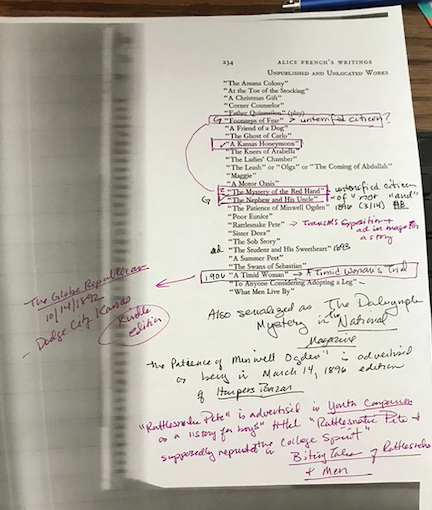

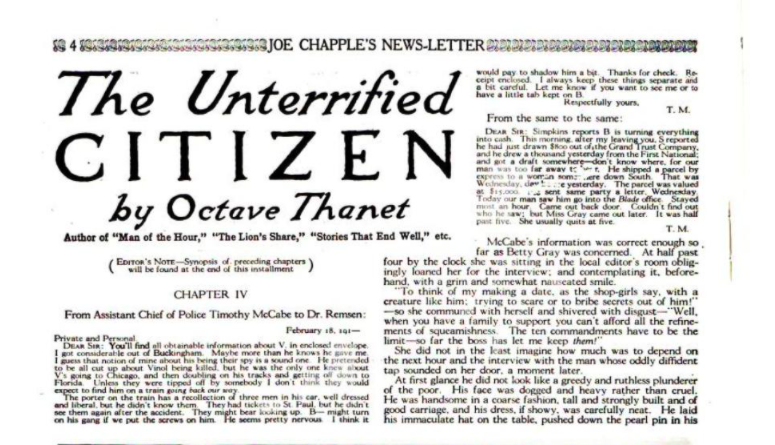

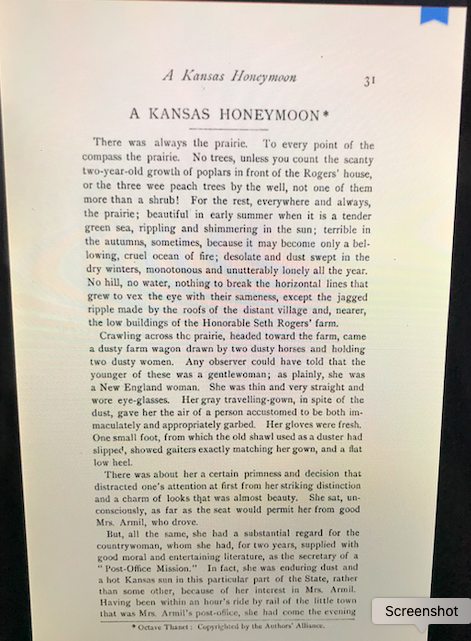

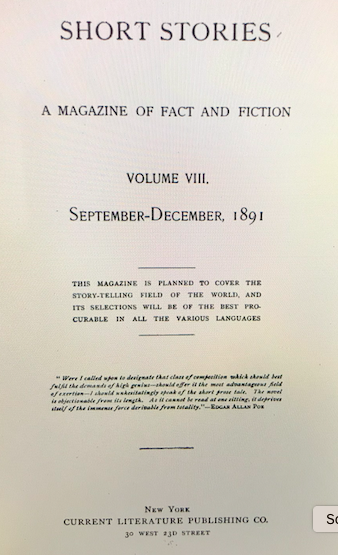

I've been using McMichael's biography to chart the timeline of Octave Thanet's stories, and yesterday, I realized there was a list in the back (see the photocopy I scribbled on above) indicating several texts he was unable to find in the 1960s. I went on the hunt to see what I could find digitally. My first find was "A Kansas Honeymoon" which was rereleased in Alfred Ludlow White's Short Stories: I also found some redundancies and errors in McMichael's list. Specifically, "The Nephew and His Uncle" should actually be "The Nephew of His Uncle" and "A Timid Woman" should be "A Timid Woman's Trial." I did find "A Timid Woman's Trial" on Amazon for 99 cents (snagged it) and found it in a Dodge City's The Globe Republican, from October 14, 1892. Ads for other stories like "Rattlesnake Pete and the College Spirit" (yet another inaccurately reported title from McMichael) showed up in publications like Youth's Companion as upcoming "stories for boys," but I have yet to successfully find a copy (If anyone out there finds a copy of Biting Tales of Rattlesnakes and Men by James William Jewell in PDF, let me know if that OT story is in there, ok?). I also spotted ads for "The Patience of Minwell Ogden" in the March 14, 1896 issue of Harper's Bazar (they still spelled it that way in 1896--that's not a typo). As luck would have it Cornell has the issue from March 7 and the one from March 21, but not for 3/14. Perhaps my most exciting find yesterday, though, started with this listing from the Newberry Library. I noticed the discussion of "several variants of a mystery," which was intriguing. Looking at McMichael's list, I see "Footsteps of Fear" and "The Mystery of the Red Hand" are listed separately. The Newberry seems to show them as variations of the same story, however.  And, as luck would have it, the ad for Chapple's News-letter seems to confirm that The Unterrified Citizen is a serialized version of "The Mystery of the Red Hand." Furthermore, I found The Dalrymple Mystery serialized in The National Magazine after it appeared in Chapple's. The opening chapter is the same.

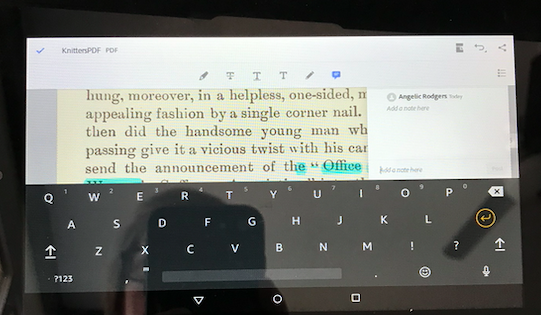

So, not a bad haul for a day's work: that removes five "unlocated" entries on McMichael's list (and potentially six, if I ever find "Rattlesnake Pete and the College Spirit"). I did find an ad for "The Student and His Sweetheart" dated 1893, but have not found the text yet. I debated whether to share this here, or in my regular old blog, but decided since the issue came up as part of my work on this project, it belongs here. One of the wonderful things about the digital age is that long-forgotten texts are often available as scanned first editions. This means that I can read the book as it looked to contemporary readers, which I find exciting. While I do own a few first editions of Octave Thanet's books, I don't (obviously) want to highlight and annotate the physical copies. So, I needed to come up with a solution. One option that appeared yesterday was to purchase an Onyx Nova 2 or 3 (the 3 just released and is available in color for $400+). Nova 2's run Android 9 and Nova 3's run Android 10. From the reviews I found this morning, they work well without taking forever to refresh when you turn the page, and you can search your notes. My problem is that our household already has multiple tablets, eReaders, and laptops (and a huge desktop). I've been using the iPad to read Knitters in the Sun, but wound up downloading in ePub so I could highlight and make notes to the text. The problem with that is that ePub and other converted formats contain tons of errors. While Knitters in the Sun is pretty "clean" as a converted text goes, the next one on my list isn't. So, I knew for my next read (and who knows how many others) that I would need to go back to the PDF scans. Using multiple devices to read and take notes is not appealing to me. Neither is shelling out another $300-$400 on another device. The reMarkable tablet allows me to "write" on the PDF but there's a horrible lag time when I turn a page. Adobe Digital Editions app allows me to see the scans and read, but again, there's a lag on turning pages and I can't annotate. The solution? Adobe Acrobat. I can't put it on the ancient iPad we have, but I do have Google Play on my Fire Tablets. And, Acrobat allows me to highlight, draw, and add typed notes to the original scans. Here's my 2015 Kindle Fire 7 inch with a note box open and some sample highlighting. I paid $50 for this tablet some five years ago and it still has great battery life, is less cumbersome than the iPad, and if it dies, I can easily afford to replace it. Update! After finding some texts only available at the Google Play store, I realized that the Google Play reading app also shows the scanned page and offers highlighting and notations. As a bonus, it saves those notes and highlights and syncs them with your Google Drive. In addition to the syncing, the highlighting is less choppy (neater) and the notes are easy to spot.

Louise (Bishop’s daughter) and Colonel Martin Talboys are talking at the start of the story. On pages 56 and 57, there’s a good bit of talk about the south. Specifically, Louise mentions that her experience of Southern manor houses and plantations has always been a bit of a letdown: I expected to see the real Southern mansions of the novelists, with enormous piazzas and Corinthian pillars and beautiful avenues; and the white-washed cabins of the negroes in the middle distance; and the planter, in a white linen suit and a wide sraw hat, sitting on the piazza drinking mint juleps. Well, I don’t really think I expected the planter, but I did hope for the house. Nothing of the kind. All I saw was a moderate-sized square house, with piazzas and a flat roof, all sadly in need of paint. Now, I’m like Betsey Prig; ‘I don’t believe there’s no sich person.’ It’s a myth, like the good old Southern cooking (p. 56). Martin assures her: Oh, they do exist . . .There are houses in Charleston and Beaufort and on the Lower Mississippi that suggest the novels; but, on the whole, I think the novelists have played us false. We expect to find the ruins of luxury and splendor and all that sort of thing in the South; put in point of fact there was very little luxury about Southern life. (p. 56). This exchange is interesting for multiple reasons. In terms of the story, Louise rejects Talboys in part because she finds him uninteresting and too short (the name is punny for that reason). Secondly, in Thanet’s own fiction, she more often focuses on the lower classes and those in rural Arkansas than she does any sort of idealized plantation imagery. The main plot summary: Demming (the vagabond) constantly lies and gets money out of Louise’s father, the Bishop. The story opens with such a lie about his wife dying and his need of a coffin. We find out, upon the Bishop, Louise, and Talboys visiting his cabin, that the wife is quite alive; the coffin was for a black neighbor, Mose Barnwell, whose wife had passed (p. 68). The Bishop and Demming make up, and it turns out that Demming has a relative in Charleston who has left him property and sent him money to travel there. After spending all of his money at the pub buying rounds, Demming is rescued by Talboys who is leaving town after Louise rejected him (Talboys buys Demming a new train ticket). The train collides with a freight train and in the wreck Demming breaks his leg. The bishop is trapped and no axe is on the train. Talboys runs to get one, and arrives just in time as Demming is prepared to shoot the bishop to prevent him from suffering. Talboys gets the bishop free, and the three return to Aiken. Demming has surgery to amputate his leg, but he dies after he patches things up between Louise and Talboys. Louise promises Demming that they will look after his wife. McMichael notes that the story is remarkable for the use of conventions of other local color fiction filled with romance and strange people in a unique setting, it was hardened with dialect that often required explanatory footnotes to lead readers through the jungles of apostrophes and phonetic approximations. It was Alice’s first use of extensive dialect transcriptions, and it revealed not only her attempts at realism but also the perseverance and tolerance that magazine writers and editors could expect from their readers (pp. 93-94). |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed