Basic summary: The story opens with one-armed Jeff Griffin carrying home a tiny coffin for the recently dead baby of Cap'n Bulah, the love of his life (and distant cousin). Bulah is the widow of Sam Eller (the baby's father). Bulah still runs his boat, as she is determined to pay off his debts. When her baby dies, she is inconsolable. On his way to show her the coffin, Jeff picks up Nate who tells him about a baby left at the plantation store. The widow Mrs. Brand is caring for the baby, and Jeff picks her up and takes her to his house where Bulah is still rocking her dead child. When he sets the boy on the floor, he cries for his mother and Bulah shakes herself out of her stupor, allowing her own baby to be buried. Jeff and Bulah begin to care for the child in February. In October his mother, a traveling cotton picker, returns and demands her child back. The widow Brand saves the day when Headlights (real name Sabrina Mathews) tries to force the sheriff to tear the boy--now called Jeffy--from his foster parents. She demands board, cost of clothing, and cost of housing for the last eight months at a total of $27 to be paid in six months or Jeff and Bulah retain custody forever. Mr. Francis draws up a contract--thus, the "Mortgage on Jeffy." Headlights demands the right to pay the debt early. She returns when Jeffy has come down with a fever and they fear he'll develop pneumonia. He's always been puny, which was one of the reasons they refused to let her take him, as he would die without care he needs--care his mother can't give him on the road as part of a cotton-picking team. Jeff sees her in a stupor in the swamp and takes her home with him. Headlights realizes that she can't care for the child properly and makes Jeff and Bulah agree to marry and they can keep him. She develops pneumonia and dies. Before she does, she pulls a leather pouch from her neck and says it is for Jeffy. Inside is the $27 and a copy of the mortgage. Notes: I'm intrigued by the name "Headlights" here. It seems really odd. Also, I am not sure that this is as clearly sentimental or classist as McMichael seems to think. Headlights, just as with Dosier and Chaney before, has deep emotional feelings and ties to her son, even as she leaves him at 17 months at the store. Carrying a child that small from job to job couldn't be easy, and likely the child would have died. The whole mortgage situation is also weird. Obviously, Jeffy is not a slave or treated as property by Bulah and Jeff, but the idea of owning other people is definitely at play here. There's some weird "owning you to take care of you" stuff going on here (as in, you're being treated as property for your own good).

0 Comments

Basic summary: This is an oddly cute story about a Governor at home who is approached by the mother of Fritz Jansen, a man sentenced to hang for the murder of his fiancee. The woman is German and speaks very little English. Luckily, the Governor's wife, Annie, is fluent in German. The woman tells of walking 15 miles to get to him before her son's execution. She asks for a pardon, as her son is a good man who would never do such a crime. Annie pleads with her husband to stay the execution--if he's truly guilty, why not give him a life sentence so his mother doesn't suffer. The Governor counters that to do so would be worse for Fritz's mother than executing him. If she hates the Governor, Very well , so be it . She will still have her memories of his youth to console her, and her very conviction of the injustice of his fate will be a comfort to her; while, on the other hand, if I release him, he will dissipate all her illusions, neglect her, ill-treat her, very likely spend every cent of her hard earnings, and at last convince even that trusting soul what a brute he is. It is the truest kindness to her to refuse." (Thanet, 299) The day after Fritz is hanged, the mother returns with her son, Fritz. It turns out there were two men with the same name, and her son was never arrested. Because he doesn't want to share the name with such a bad man, Fritz and his mother come to the Governor for a name change. Annie declares he'll change the name as a wedding gift to Greta and Fritz. The wedding is briefly described and the story ends with Annie and the Governor relieved at the outcome.

In the end, the Governor makes the comment that he would have been so embarassed if he'd followed Annie's "feminine" mind and pardoned the evil Fritz. He asks her who was right, and she exclaims, "Both of us" (Thanet, p. 299).

Basic Summary: Milt Bedford plans to take over Sycamore Ridge's post office and oust the former northerner named Captain Leidig, the current Postmaster. General Throckmorton can't bring himself to break the news to Leidig that he is being replaced. That night, the Great Fire breaks out, and Leidig and his "chemical engine" (Thanet, p. 273-4) save the post office and the town from the blaze. Leidig is gravely injured in the fire, and Throckmorton and the town think there is no way Leidig will be removed from his post after saving everything. Unfortunately, Bedford is installed as postmaster as Leidig is on bedrest and dying. His former assistant, Roz Miller, keeps up the charade that Leidig still holds the post, unable to break his heart as he lay dying. When Bedford intercepts a note to the office by Leidig before his assistant can, he goes to visit the ill-man whose job he took. He's tender-hearted enough to continue the charade and spares Leidig's feelings. The title of the story comes from General Throckmorton, the district's congressman. While citizens discuss how wonderful Leidig is as postmaster and how it's a shame he lost the post, Throckmorton says Leidig was an idiot to start with. Not only was he a humane officer in the military who treated political opponents well (Throckmorton being confederate military), but he also was brilliant and had patents. Had he kept inventing, he would have been rich. Instead, he was an idiot: Now I , gentlemen," said Throckmorton,“ I call Hiram Leidig a plumb idiot.” The crowd simply gasped; Throckmorton being Leidig's closest friend, and a man not to desert a friend under stress of weather, "Yes, gentlemen, a plumb idiot,” he repeated, in his gentlest tone; “here he is. He could have made a fortune had he stayed in the manufacturing business. When the war broke out he was getting a salary of twelve hundred dollars, and he had invented half a dozen little tricks, and got patents on them, and saved ten thousand dollars. . . Well, what does the government or the party give Leidig for his long services? You all know. Half a dozen times he has been within an ace of getting bounced by one party or the other, and now he is going to be pitched out in good earnest by his very own party because he can't be trusted to run the office as a party machine, and Milton Bedford can! That's the size of it. Now, a man who will squander his chances of fortune and the best years of his life on a government or a party which kicks fidelity every time is - a plumb idiot!" Themes: The North is not always the enemy and service is more important than wealth. We later find that Throckmorton "loved Leidig. The two men had been like brothers since the Federal soldier saved the Confederate soldier's life and cared for him in prison during the war" (Thanet, p. 268). When he confronts Leidig about his service and how he should have stayed in business, Leidig responds by saying: Look here, Marion, the way you felt for the South, I felt for my country, our country. [bold mine] And I had this kind of a feeling: the way to obliterate the war is to fetch people close together . You stay here awhile, old fellow,' says I, “and do your best for the old flag. Be a decent fellow, for they are going to sample the North by you. Don't go at them ramping and roaring, and shaking your opinions in their face like a red rag, when they're just naturally sore all over. Here's a chance,' says I, “ to do your country better service than you did in the war" (Thanet, p. 272). The story ends with the narrator suggesting that maybe Leidig was right about how it is an honor to serve, or "perhaps, again, he may be right some day" (Thanet, p. 284).

Notes: Roz Miller always takes Christmas week off, as he is "obliged" to get drunk that week. Leidig tells him that it's improper for a postman to be drunk, so every year, he suspends him that week. To keep up the ruse while Leidig is dying, he stays sober. We find out he also has a wooden leg, which is never explained, but French did later lose a leg due to complications from diabetes and was wheelchair bound in her later life in Davenport.

Basic summary: A tenant farmer is on trial for killing a con man. The case is up in Lawrence County (abbreviated as L---- County in the original text). The accused, Dock Muckwrath, shot a man who "changed cards" on him. The general public figure since Dock lost all of his money in the world ($50) the killing was justified.

The jury ultimately lets Muckwarth off--not because they think he's not guilty, but because the foreman reveals how horrible convict camps are: "The doctor , who had the medical eye for com plexion, observed that Captain Baz was certainly very pale . “ My opinion, sir," said the captain , slowly,“ is that, in the present state of convicts in Arkansas, if you don't find the man not guilty you had better find him guilty enough to be hanged" (Thanet, p. 239). He goes on to explain that, "He told me, what I found was true, that the whole convict system is a money-making affair. They are all on the make. The board, commissioners, contractors, lessees, wardens, and guards, — they all just naturally squeeze the convict" (Thanet, p. 242). Captain Baz Lemew relates how he was in one himself, and how he blew the whistle on the abuses in the camp by passing a note to an inspector's sister in town. The horrible abusive Warden Moss turns out to be the scoundrel Muckwrath shot. So, the jury looks at the case as one where justice was meted out by the killing. Characters of note: Mr. Phillipson: The prosecutor. He asks "why a State so beautiful, so fertile, so attractive to every class of emigrants, is neglected" (Thanet, p. 226) and argues "It is because the old taint of blood and crime clings to our garments still" (Thanet, p. 226) and that they must convict to ensure that other people realize "that there is not in all this broad land a more peaceful, law-abiding section than ours, or a section with better enforced laws" (Thanet, p. 226). His argument is important as there is a Northerner in the audience, as Dr. Redden says to the others: "Phillipson was right; it discouraged immigration. He had seen Mr. Thornton (the Northerner) in court. They all knew he was fixing to build a canning factory. Was he likely to do that if they convinced him that any of his men could get mad and pop away at him with a gun, sure of getting off? It looked like they might lose their factory, may be their railroad, if they monkeyed with the verdict. Let them remember their oaths and the law; that was all he asked" (Thanet, p. 235). Dock Muckwrath is described as: "His face was of a type common in Arkansas among the renters, where the loosely hung mouth will often seem to contradict fine brows, straight noses, and shapely heads. One could see that he was wearing his poor best in clothes, namely, a new ill-fitting brown coat, blue trousers, rubber boots, and a white shirt with a brass collar-button but no necktie" (Thanet, p. 225). Captain Baz Lemew: The jury foreman. Dock is one of his renters (sharecropper/tenant farmer), and during deliberations, we learn that he was once Trusty, No. 49. He is now married to the inspector's sister--the same one he passed the note to in town. Dr. Redden: "desired a conviction ardently. His motives were the cleanest in the world. Of the new South himself, he believed in immigration, enterprise, and their natural promoters, law and order" (Thanet, p. 222). Thornton: Northerner in attendance at the trial who is planning on building a cannery in L----- County. His reaction to the verdict: "The Northerner, who was with Phillipson, laughed outright. 'They do seem pleased,' said he. 'See, Phillipson, there go the interesting family home together in one of the jurymen's wagon; Muckwrath is kissing the baby. Well, I confess I am glad he does n't have to go to your confounded penitentiary" (Thanet, p. 261). Notes on setting: The town used to be prosperous, but the railroad passed it by. Now, it is struggling, hence the importance of Thornton's cannery coming. The court is held in Barker's store, as the courthouse burned down some time ago. Interesting mix of business and law, of course. Given that so many of her Arkansas stories take place in spaces where boundaries are blurry and often circles of influence overlap (a judge sees a citizen in his home, a store becomes a court, people live on plantations--the very epitome of business and personal life being merged--people are property). Also, next door to the court/store is the local bar, Milligan's. Notes on dialect/language use: Trusty=Trustee in today's parlance. Thanet's Arkansas stories often deal with race, and characters often use the "N" word when referring to people of color. This is problematic, but to consider the characters' use of the term as a sign of Thanet/French's own racism is simplistic, in much the same way that banning The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for Huck's early use of the word is problematic. We cannot fully explain Alice French's views on race on the characters' use of the word. That's not to excuse the use of the word entirely, nor is it to say that Alice French did not have racist views herself. It is--much like the issue of her being an anti-suffrage activist in real life while also having her own wood working shop, her own photography studio, and being coupled with another woman and being out in her Boston Marriage on an old plantation in Arkansas--complicated.

Basic summary: This story focuses on a feud between two neighbors, Luther Morrow and Dock Haskett. They had been feuding about who was the better shot, and when Morrow's dog, Jerusalem Jones, stole a ham from Haskett, he tried to shoot the dog and wound up hitting Morrow instead. Morrow shot Haskett in the shoulder as a result and the two are feuding. The two men decide to have a duel in the woods near where Haskett's wife is buried, but their children bring them back together.

The story opens with Minnie Haskett learning how to bake brown bread from Miss Dora. She's taken over the domestic duties at the small house since her mother died, and she loves her father so much she wants to cook well for him and her younger siblings. Even though Dock and Luther are fighting, Minnie and Doshy love each other and Minnie wants to teach Doshy how to make brown bread. Dock gives his consent, as he has no quarrel with any of the Morrows other than Luther. The two men are in the woods ready to shoot it out when they hear the two girls talking. They find a place in the brush to watch them and see them baking bread over a small fire. The two girls talk about how kind their fathers are as they work, and how much they love them, softening the men's hearts toward each other. Jerusalem Jones is playing with a small pig, and wild adult hogs come to the pig's defense. In the melee, the bread is disturbed but Morrow shoots the hogs and the day is saved--as is the "loaf of peace." Characters: Aunt Callie (seen in other stories), Miss Dora, Miss Carroll, Hasketts (Minnie and Dock), Doshy and Luther Morrow (Doshy is named after her mother, Mindosha), and, of course, Jerusalem Jones.

Basic summary: Characters: Mrs. Ponder, Mrs. Higgins, Miss Maine, Dosier, Chaney The story is set in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Dosier, a widow, works in the baths and has an invalid sister--Sist' Chaney. Dosier has a black silk gown and Chaney covets it. Mrs. Ponder says, ". . .she doesn't go out of the house once a year. If you please, ladies, she's plumb crazy for a black silk gown. Ever since Dosier got hers, she's been craving one" (Thanet, p. 142). Despite Mrs. Higgins objections that Dosier should not entertain Chaney's desire for the gown as they are poor and need the money for other things, the other women don't seem to feel the same. Dosier is not only highly praised among the three women in the baths; "Frequently she met acquaintances, black or white. They all greeted her with a degree of respect" (Thanet, p. 143). When Dosier arrives home, Chaney is crying and the doctors deliver the news that she can no longer leave the bed and is dying. Dosier realizes she can't go back to work and leave her sister unattended. Mrs. Ponder goes to visit, and she tells Higgins and Maine all about it. Mrs. Higgins thinks Chaney should be "glad to go" (Thanet, p. 151). Miss Maine suggests that Chaney should want to be with her dead husband, to which Mrs. Ponder reponds "I don't guess he counts much. He was a trifling no-'count n____, who wanted to wear his Sunday clothes every day, and sit in the store-doors and ogle the yellow girls. I reckon he wasn't any too kind to her, either, ayfter she got too sick to earn money for him to spend" (Thanet, p. 152). The story is remarkable largely for what it says about race relations. On page 143, there's a description of main street: At that hour of the day the Hot Springs main street is a picturesque scene, a kaleidoscope of shifting figures, all tints of skin, all social ranks; uncouth countrymen on cotton wagons; negroes in cars drawn by oxen or skelton mules with rope harness; pigs lifting their protesting noses out of some carts, fowls squawking in others; a dead deer flug over a horseman's saddle; modish-looking men and women walking; shining horses curveting before handsome carriages; cripples on crutches; deformed creatures hugging the sunny side of the street before the bathhouses; pale ghosts of human beings in wheeled chairs,---so the endless procession of wealth or poverty or disease or hope oscillates along the winding street between the mountains." Even on her deathbed, Chaney says she'd rather have her desired black silk than go to heaven (pp. 148-9). After Mrs. Ponder suggests Dosier tell Chaney about the fine funeral she will provide for her sister, she does, inviting Miss Betty (Ponder) to go see Chaney. Yes, honey, dat so; but ef you didn't have a good time, you shall have de bigges' an' de nices' burryin' of ary cullud pusson in Hot Springs." (Thanet, p. 155) The story ends with a description of the funeral; Chaney is comforted enough by the pledge of the black silk that she dies in peace. We see Ponder and Maine discuss how peaceful and beautiful the funeral was. When Miss Maine mentions it's a shame Chaney "couldn't see her own funeral" (Thanet, p. 159) Ponder responds with "Well, I don't know; perhaps she did" (Thanety, p. 159). Take aways: The story sets up several instances where stereotypes are chipped away at. Not only do we see how intimate the interactions are between white clients and black bath attendants in the story, but we also see strength in Chaney versus Mrs. Higgins. Mrs. Higgins says she wants to die when her hands are in an arthritic flare, which is why she says--even before Chaney is clearly on her deathbed--that she doesn't know how Chaney stands living. It's a nice touch, then, that Dosier shares gifts Mrs. Higgins has given her with Chaney for the funeral, since Higgins gripes about how "silly" Chaney is for coveting a black silk gown when she obviously has more important things to worry about. The love the sisters share and how Dosier would do anything for her sister is the obvious focus here. The doctors have a brief conversation about Dosier's grief--one mentioning that it seems odd to him that Dosier doesn't seem relieved to soon be on her own after taking care of her sister for so long: "'Bracing up,' muttered the youngest man. 'She feels bad. Queer, too; the woman's always been a burden to her.'" Dr. Le Verneau, irritated, responds, "'That's all you know about it, . . . Don't you suppose she's fond of her kin? That poor soul there has lived with Dosier for twenty years." (Thanet, pp. 146-7). Ponder and Le Verneau seem to be the most sympathetic and understanding of Dosier and Chaney, seeing them as humans with the same level of emotional capability as themselves. Side note: A lot of talk about chewing gum as a habit at the beginning of the story. Also, a bit of discussion of how Dosier's late husband shot a gangster--a good bit of local color writing about Hot Springs. Late in the story, we find Mrs. Ponder is hooked: " Gum had become a sort of intellectual motor to Mrs. Ponder, who never felt her mind really working without a simultaneous action of her jaws" (Thanet, p. 153).

Basic summary: This is the story of Atherton--both the Western town and the man it was named for. Katy and Tom Ransome, young lovers who married despite family objections, are lured to Atherton for Tom to become the editor of the paper, The Citizen. Once there, they meet Atherton--the first mayor of the town, his wife (the widow Bainbridge and her daughter), and Renee, the Louisiana native who also followed the Westward expansion.

Initially, Katy is put off by Atherton, but the more she learns about him, the more she likes him. Over and over again he puts himself at risk to help others--first, it is the man who confronts him for putting him out of business. We learn later that he hired the man at a salary higher than he ever made when running the business, though, and that the business failing was a blessing. After his wife and children died of Cholera, he married the widow Bainbridge who was destitute after her own husband died. Her daughter Rose tried to stab Atherton with a penknife on their wedding day, but he was later her friend. Atherton has gone so far as to guarantee currency, and when the bank goes bust, he is elected out of office. His wife dies in a carriage accident, and he winds up having a fit of apoplexy. Katy and Tom move, and when they return ten years later, the town has been renamed and it is only by finding the monument Atherton had built for his first wife and three lost children that they realize they've found his grave, as well. Items of note:

Notes:

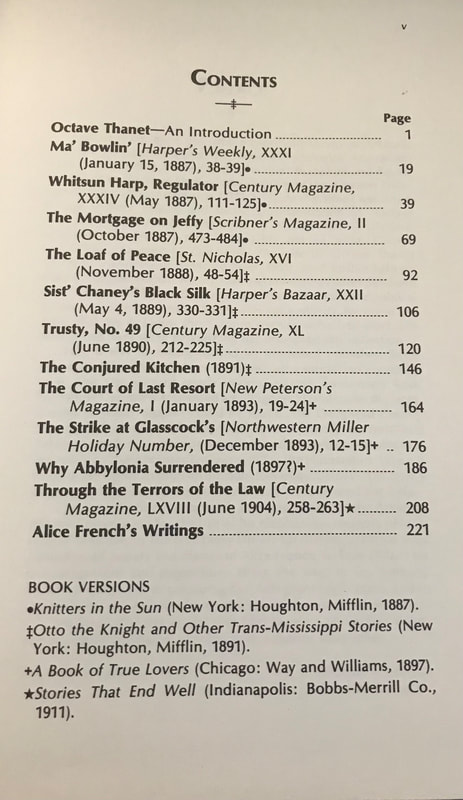

I was excited to begin Otto the Knight and Other Trans Mississippi Stories in part because of the regional focus. A few of these stories carry over characters from stories published in Knitters in the Sun. Michael B. and Carol W. Dougan's 1980 collection By the Cypress Swamp: The Arkansas Stories of Octave Thanet brings many of those stories together, although the title story "Otto the Knight" is not in that collection. Given the very light emphasis on the setting here, the omission of the story isn't completely surprising. McMichael also only mentions the story itself on page 125, indicating that it was chosen as the title for the collection solely based on the fact it was the first story. The omission is interesting, given that Lum Shinault definitely lives on the Black River in "Whitsun Harp, Regulator" and because there is the connection to getting lost in the swamp. Marty Ann searching for Boo gets lost, just as Ma' Bowlin got lost in the earlier story. Basic Summary:

|

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed