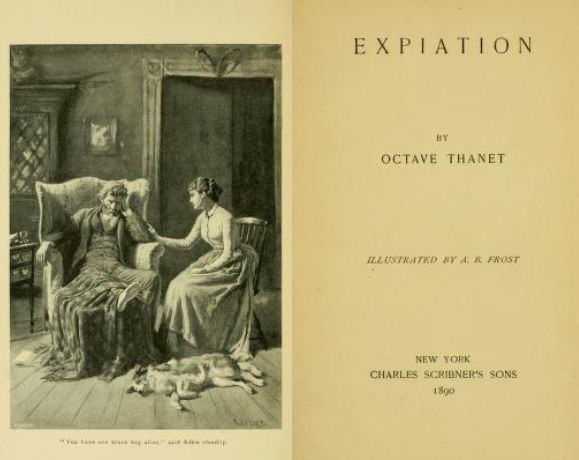

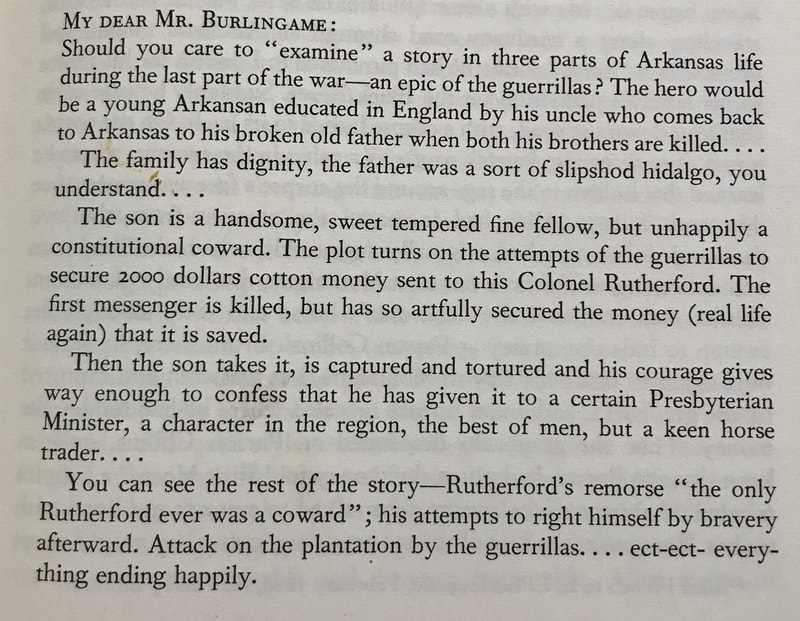

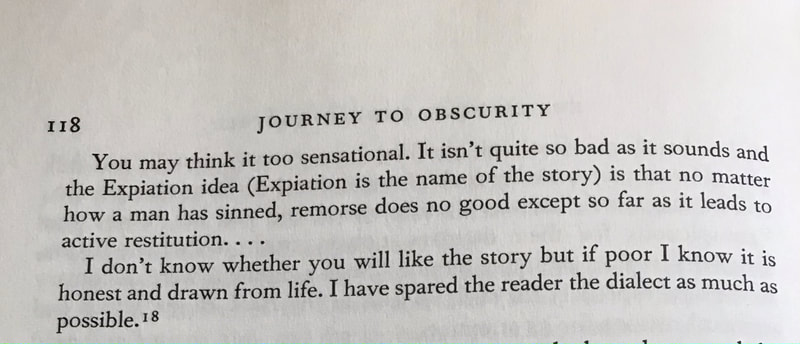

The summary in the above letter is spot on; the novel focuses on young Fairfax Rutherford, who has been living abroad with the uncle he was named for. He returns to his father's plantation in Arkansas and is immediately caught up on the robbery scheme and captured. His shame happens when he first reveals Parson Collins has the money; he feels guilty about revealing that, but is even more horrified when he thinks he's shot Collins after being burned with hot coals from the fire. The story works itself out; we later find that Collins is not only alive, but also that it wasn't Fairfax who shot him after all--it was Lige, who was aiming for Dick Barnabas, leader of the guerillas. Setting: The area around the Montaigne Plantation on the Black River. McMichaels notes it is set in 1864 (p. 118). Characters:

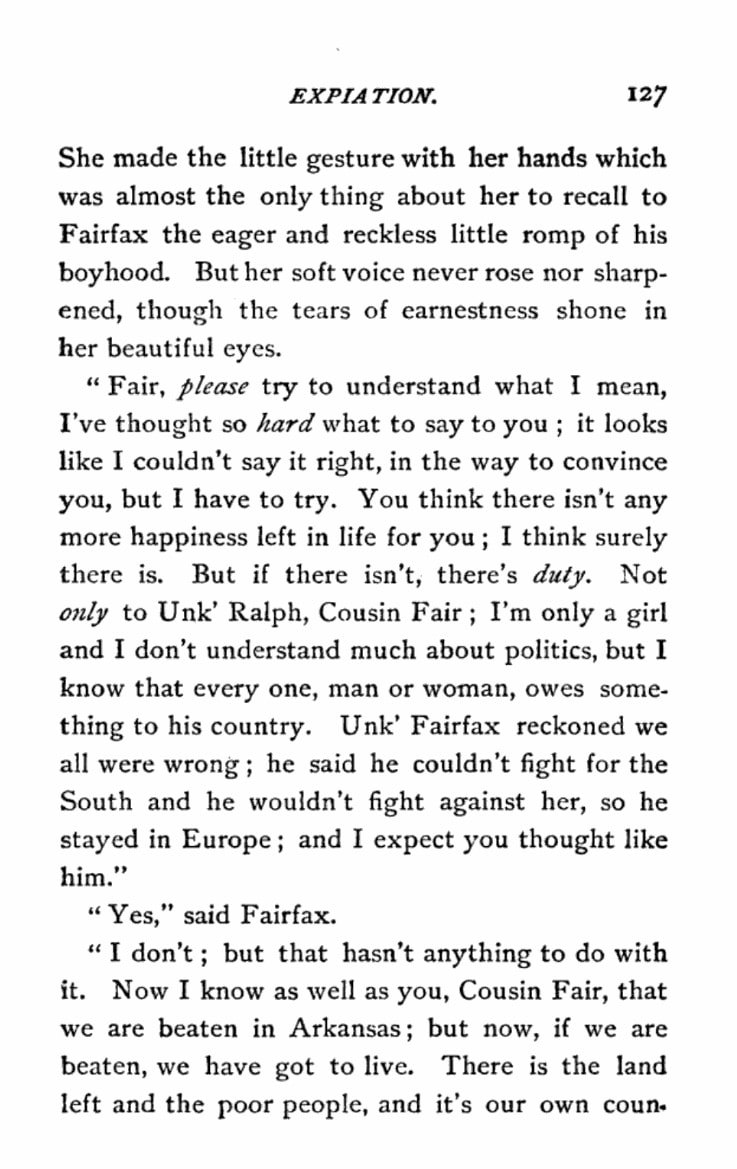

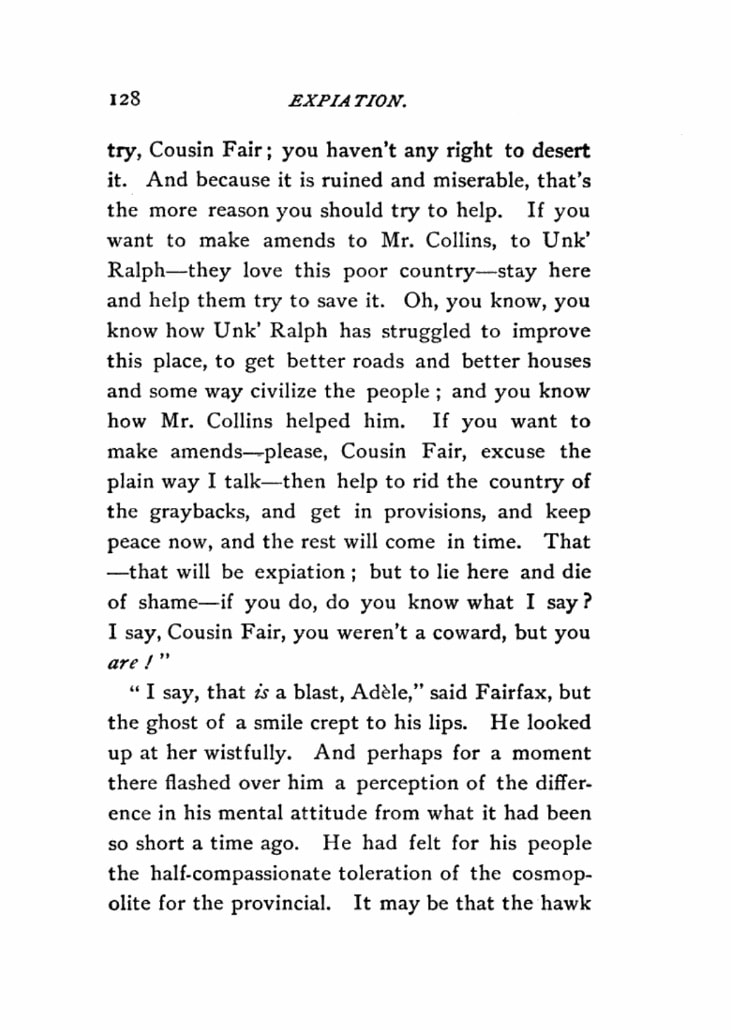

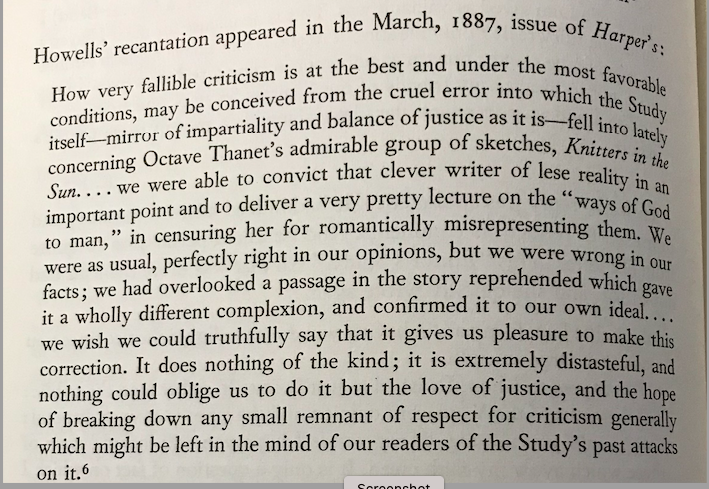

Expiation: Adele is the first to use the word "expiation" when talking to Fair about his guilt: "God won't hold you guilty for that. And even say you were guilty, guilty of the worst--well, what then? Does repentance mean despair or expiation? 'Bring forth fruits,' the apostle says, God will not despise a broken and a contrite heart: but if such a heart doesn't lead us to do something" (Thanet, p. 126). Adele continues on pages 127-128 to tell Fairfax he should stay in Arkansas and do right by Parson Collins: "you haven't any right to desert it. And because it is ruined and miserable, that's the more reason you should try to help. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country--stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country-stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends--please, Cousin Fair, excuse the plain way I talk--then help to rid the country of the graybacks, and get in provisions, and keep peace now, and the rest will come in time . That —that will be expiation; [emphasis mine] but to lie here and die of shame—if you do , do you know what I say? Cousin Fair, you weren't a coward, but you are!" Masculinity: This is a central theme as Fairfax feels the need to fit his father's image of a real man. His brothers have died, and Fairfax is the sole heir left. When Barnabas says he was a coward, it crushes Fairfax and makes the relationship with his father strained (until the truth comes out). Fairfax is a bit of a dandy, but not necessarily in a bad way. While he has funny clothes and is softer than men in the Arkansas Swamps, those traits are not seen as a failing. At the end of the novel, his refinement is mentioned and becomes a bit of an issue for Adele who thinks she can never be quite refined enough for him, but Adele winds up liking his sense of fashion and his cleanliness. On page 81, we see that Fairfax was always sensitive to fear and that even as kids Adele had a stronger sense of rationality--see below regarding childhood tales of conjure men and headless cats. Adele didn't believe they were real, but Fairfax did. Race: Aunt Hizzie: She's treated as a caricature. "Aunt Hizzie, in her white turban (economically made out of a castaway flour-sack ), with a blue apron try ing to define a waist for her rotund shape, was always a figure in the gallery when dinner was under way" (Thanet, p. 30), Her method of communication is to holler at people. Barnabas: This issue comes up not only with Hizzie and other enslaved people of color in the book but also in terms of Dick Barnabas who is described as having a "sharp profile with thin lips, curved nose, hollow cheeks, a sweeping mustache, and inky locks of hair, straight and coarse enough to warrant the common taunt that 'all of Dick Barnabas wasn't Jew was mean Injun'" (Thanet, p. 66). Early on, Colonel Rutherford is telling his wife the story of Ma'y June and says, "Dick, he was renting of me then, am - mean Jew Injun, same like he is now, and getting most his livelihood swapping horses" (Thanet, p. 41). Thanet contrasts Barnabas and Fairfax: "Their eyes met; the cruel old-race black ones, the frank brown eyes of the Anglo-American; the glitter in each crossed under the torch-rays like sword-blades , but it was the brown flash that wavered" (Thanet, p. 75). Also, Thanet uses the word "injun" again when Lige tells Sam "he had a mind to kick, but he warn't no injun, by ____" (Thanet, p. 78). "in spite of his seeming apathy, Dick's Indian blood was at boiling-point. Lige stood in front of the open window; before he had time to realize the situation he found himself sprawling on the ground outside" (Thanet, p. 92). Magic of the Swamps: Mose has freedom to travel the swamps and communicates with animals. The homestead of the French LaRouge who was killed by Barnabas and his men is the "magical" and haunted spot that Barnabas uses as home base: "on the mound to the right , which was a forgotten chief's last show of pride , an old Frenchman had built him a log cabin , where he lived alone" (Thanet, p. 77). . . "Dick told them that he chose the place because it was a spot held accursed and haunted" (Thanet, p. 78). Conjuring is mentioned when Fairfax remembers tales he was told as a child to keep him in line: "How they terrified him! That one, of the big conjure-men who threw lizards into Mammy's mother so that she died-but that was not so frightful as the one about the little black cat without a head that would come and sit by a 'mean' boy's bed and purr and purr; and , if the boy should make the least bit of noise, would leap on the bed and rub its dreadful neck against him. What a ghastly fancy! Why must he remember it now?" (Thanet, p. 81). The "now" in question is when Barnabas takes him to LaRouge's ruins. "Aunt Tennie Marlow was well enough known to Fair. She was an old and very black negress who enjoyed a great name as a bone-setter, knew a heap' baout beastis,” ushered all the babies of the neighborhood into the world, and on the strength of these gifts and of living alone was suspected to be a “conjure woman" (Thanet, p. 163). To view all of my chapter summaries and highlights, click here.

0 Comments

Basic Plot Summary: Part I: Polly Ann Shinault, wife of Lum, is out fixing the Clover Bend ferry-boat when she sees Whitsun Harp in the boat with her neighbor Boas. Harp has come by because he's heard Lum and Polly are missing a mule, and Polly acknowledges that, saying that Lum is off looking for it, but they assume it has been stolen. He proceeds to tell her his story of becoming a regulator, and how it seems like a calling from God. It's pretty clear Harp was sweet on Polly but Lum beat him to her. Harp mentions that as kids they played together and he told her everything then, which is why he felt the need to personally tell her why he had become a regulator.When he leaves, Boas tells Polly that Harp already warned Lum to shape up and to stop partying. He emphasizes the importance of Lum doing so by telling her different stories of Harp "giving a lickin'" to various people. Lum comes home for supper and when Polly tells him Harp finds him "trifflin'" Lum indicates Harp had better mind his own business. We learn that Lum helps his wife with household chores, having helped his mother because his father was 'triflin.'" We also learn that "he had married Polly Ann out of compassion" (Thanet, p. 316) when her father died. He reasoned that "Nary un waiti' on 'er neether, 'less hit ar' Whitsun Harp. Ef he don' marry her, I reckon Ihed orter. 'Tain't no mo'n neighborly.' //Whitsun making no sign, he carried out his intention" (Thanet, p. 316). In a conversation with Boas, Lum reveals the truth about his interactions with Savannah Lady. They are merely trying to make the man she loves jealous, and Lum thinks there's no harm in it. The trick works, and Morrow proposes to Savannah. Unfortunately, Lum, Whitsun, Polly, and Savannah all converge in the dry bottoms of the swamp and Harp mistakes Lum helping Savannah by giving her whiskey when she is ill to be some romantic tryst. He breaks of a switch and beats Lum. Polly sees it all and chides Lum for not standing up for himself, but she assures him she'll cook him a good dinner. Lum is ashamed and cries because he thinks Polly doesn't love him, and he's sure this was the final straw. Part II: Lum doesn't come home for dinner, despite Polly waiting. She finds a note that indicates he won't be back (Thanet, p. 328). He has taken the gun and plans to kill Whitsun Harp. "He had been beaten before his wife, his wife who valued strength and bravery beyond everything. And Whitsun, whom she praised because he was so strong and brave had beaten him" (Thanet, p. 328). He knows this is a high priority for Polly as her father, Old Man Gooden, shot a man for spitting in his face. According to Polly, "Paw hed ter shoot him" (Thanet, p. 329). Lum assumes Polly pines after Harp, and he decides that if Harp kills him, Polly won't take up with him. On the other hand, if he kills Harp, Polly will never forgive him, either. So, his plan is to "go off on the cotton-boat afore sundown. All through this wide worl' I'll wander, my lone" (Thanet, p.329). Lum (short for Columbus) crosses paths with Boas,who is dying. Boas tells Lum he's come out to warn Harp that some other men are coming to kill him. Boas killed another man a few years back, and ever since he's been haunted by it. He fears going to hell, and he hopes that by warning Harp, God will give him mercy. Unfortunately, he's too weak to go all the way across the swamp and he begs Lum to do it for him. Lum does, but he tells Harp that as soon as Boas dies, he will kill Harp. Harp, upon hearing the truth about Savannah, swears he'll make it up to Lum and Polly, but Lum says there's no way he can. It takes three weeks for Boas to die and Lum acts weird, taking to the woods mostly. Polly worries about him and follows him, but she's not sure what to do and just fears he's gone mad. When Boas dies, Lum joins Harp at the grave and tells him he's still going to kill him and where to meet after the funeral. Harp asks Lum to meet him at the plantation store first, and he does. Harp makes things right by admitting to being wrong and apologizes. He and Lum shake hands, and Lum decides to go squirrel hunting. Meanwhile, Polly notices Lum's boat is gone and she follows him to Clover Bend (using Boas' boat). She hears a single shot and runs towards it, finding Harp dead on the ground, a smile on his face. Lum is nearby, but he tells her the story of how Harp made things right and that it wasn't he who shot him. He tells Polly he'll leave her to her goodbyes, and she realizes he thinks she loves Harp. It turns out she never loved anyone but Lum, and the story ends with them embracing, Harp's dead, smiling body still on the ground. Perhaps you will excuse my mentioning that Whitsun Harp is almost entirely a true story. Harp lived and died as I have tried to picture and Boas was haunted as I have described and (although not in Clover Bend) I know of a Lum saved as Shinault was. This is no excuse for me if I haven't made the story real; I only mention it to show that I have no such notions as you impute to me; but am as uncompromising a realist as lives. I have tried not to idealize my friends of the Cypress Swamp, one atom . . .

Basic Plot: Bud Quinn and his wife Sukey live in Clover Bend. Bud was almost hanged on the day Ma' Bowlin' was born, as William Ruffner thought he had murdered his boy, Zed. Zed disappeared eight years ago, and rumor was that Bud killed him and fed him to the hogs. Sukey saved him that day by reasoning with the men (hooded klansmen, it appears) that Bud didn't have a mark on him, and he would have if he'd killed Zed who was larger and stronger than he was. The story opens with Mrs. Brand, a widow from Georgia, visiting Sukey as she finishes a new dress for Ma' Bowlin'. Sukey makes sure to instruct her daughter not to get the gown dirty, and the girl promises before setting out to the plantation store to meet her father to show him her new dress. Bud arrives home alone, and a search party begins looking for the girl. Bud was ashamed of Ma' Bowlin's feeble-mindedness and never cared for the child; upon seeing how upset Sukey is, though, he realizes he, too, loves Ma' Bowlin.' He goes searching for her, and he and Ruffner find her--and Zed. The gown is clean and the family is reunited. She was a baby ; a girl, when he wanted a boy; she was a toddling little thing who wouldn't learn to talk, but used queer sounds of her own for a language; he had a notion that it was this which first gave him his repugnance to the child . She was a girl whose feeble mind was a judgment ; then he slowly grew to hate her . He didn't know whether he hated her now or not ; he only knew that if Sukey wanted her so bad, she must have her. (Thanet, p. 252) Interestingly, when she appears on Zed's boat, she's cured: Her face looked like an angel's to him in its cloud of shining hair; her eyes sparkled, her cheeks were red, but there was something else which in the intense emo tion of the moment Bud dimly perceived — the familiar dazed look was gone. . How the blur came over that innocent soul , why it went , are alike mysteries. (Thanet, p. 264)

Basic Plot:

This story covers an interesting relationship between and a strange Countess an old childhood friend who has recently been widowed. The countess has taken a job to help support the window and the focus of the story is on the Bailey family. The husband and the Bailey family is a communist head because of his principles has been out of work. His wife comes to the two women and asks for assistance. Bailey refuses to give up his affiliations with the union and the Countess refuses to hire him on without the promise that he will not unionize and strike. Within this story the countess makes two offers to employ Bailey, and she’s turned down both times. The Bailey family moves to Chicago where the countess later has to journey in order to settle the conditions of her husband’s will when he dies. She arrives on the day of The Railroad Strike of 1877 in Chicago and sees Mrs. Bailey shortly before she is trampled and shot during the riots. Coincidentally, she winds up in the same room with Mr. Bailey as they bring in the body of his dead wife. Bailey accuses the countess of murdering his wife, and she denies the accusation, reminding him that she offered him a job twice. The story ends with neither agreeing. This story is yet another example within this collection of Thanet bringing together opposing social and economic status people into a stalemate. The story is remarkable mainly for this, but also for the depiction of the relationship between the countess and her living companion. |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed