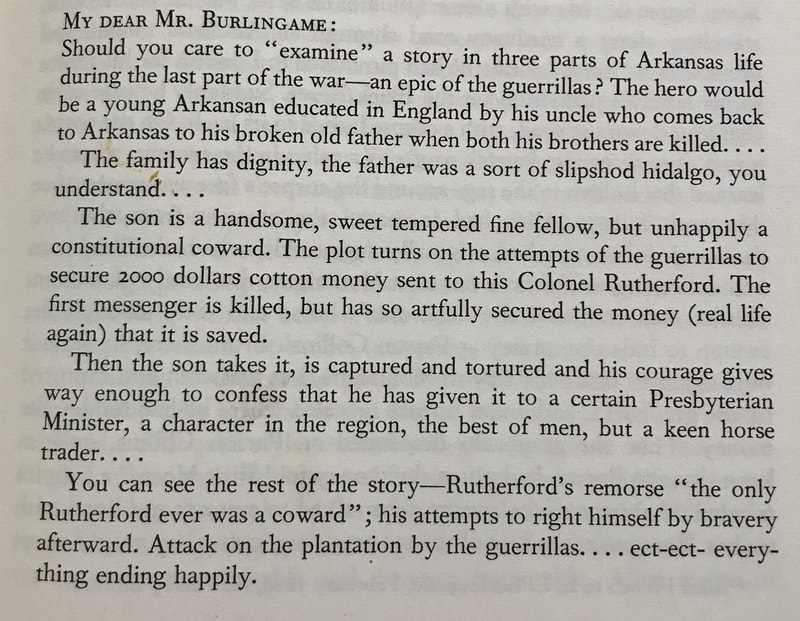

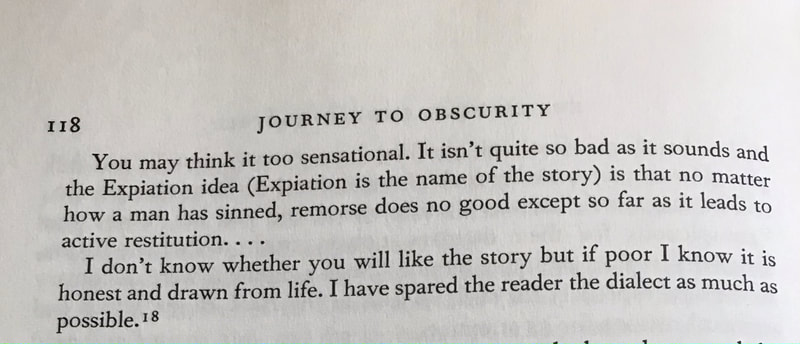

The summary in the above letter is spot on; the novel focuses on young Fairfax Rutherford, who has been living abroad with the uncle he was named for. He returns to his father's plantation in Arkansas and is immediately caught up on the robbery scheme and captured. His shame happens when he first reveals Parson Collins has the money; he feels guilty about revealing that, but is even more horrified when he thinks he's shot Collins after being burned with hot coals from the fire. The story works itself out; we later find that Collins is not only alive, but also that it wasn't Fairfax who shot him after all--it was Lige, who was aiming for Dick Barnabas, leader of the guerillas. Setting: The area around the Montaigne Plantation on the Black River. McMichaels notes it is set in 1864 (p. 118). Characters:

Expiation: Adele is the first to use the word "expiation" when talking to Fair about his guilt: "God won't hold you guilty for that. And even say you were guilty, guilty of the worst--well, what then? Does repentance mean despair or expiation? 'Bring forth fruits,' the apostle says, God will not despise a broken and a contrite heart: but if such a heart doesn't lead us to do something" (Thanet, p. 126). Adele continues on pages 127-128 to tell Fairfax he should stay in Arkansas and do right by Parson Collins: "you haven't any right to desert it. And because it is ruined and miserable, that's the more reason you should try to help. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country--stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country-stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends--please, Cousin Fair, excuse the plain way I talk--then help to rid the country of the graybacks, and get in provisions, and keep peace now, and the rest will come in time . That —that will be expiation; [emphasis mine] but to lie here and die of shame—if you do , do you know what I say? Cousin Fair, you weren't a coward, but you are!" Masculinity: This is a central theme as Fairfax feels the need to fit his father's image of a real man. His brothers have died, and Fairfax is the sole heir left. When Barnabas says he was a coward, it crushes Fairfax and makes the relationship with his father strained (until the truth comes out). Fairfax is a bit of a dandy, but not necessarily in a bad way. While he has funny clothes and is softer than men in the Arkansas Swamps, those traits are not seen as a failing. At the end of the novel, his refinement is mentioned and becomes a bit of an issue for Adele who thinks she can never be quite refined enough for him, but Adele winds up liking his sense of fashion and his cleanliness. On page 81, we see that Fairfax was always sensitive to fear and that even as kids Adele had a stronger sense of rationality--see below regarding childhood tales of conjure men and headless cats. Adele didn't believe they were real, but Fairfax did. Race: Aunt Hizzie: She's treated as a caricature. "Aunt Hizzie, in her white turban (economically made out of a castaway flour-sack ), with a blue apron try ing to define a waist for her rotund shape, was always a figure in the gallery when dinner was under way" (Thanet, p. 30), Her method of communication is to holler at people. Barnabas: This issue comes up not only with Hizzie and other enslaved people of color in the book but also in terms of Dick Barnabas who is described as having a "sharp profile with thin lips, curved nose, hollow cheeks, a sweeping mustache, and inky locks of hair, straight and coarse enough to warrant the common taunt that 'all of Dick Barnabas wasn't Jew was mean Injun'" (Thanet, p. 66). Early on, Colonel Rutherford is telling his wife the story of Ma'y June and says, "Dick, he was renting of me then, am - mean Jew Injun, same like he is now, and getting most his livelihood swapping horses" (Thanet, p. 41). Thanet contrasts Barnabas and Fairfax: "Their eyes met; the cruel old-race black ones, the frank brown eyes of the Anglo-American; the glitter in each crossed under the torch-rays like sword-blades , but it was the brown flash that wavered" (Thanet, p. 75). Also, Thanet uses the word "injun" again when Lige tells Sam "he had a mind to kick, but he warn't no injun, by ____" (Thanet, p. 78). "in spite of his seeming apathy, Dick's Indian blood was at boiling-point. Lige stood in front of the open window; before he had time to realize the situation he found himself sprawling on the ground outside" (Thanet, p. 92). Magic of the Swamps: Mose has freedom to travel the swamps and communicates with animals. The homestead of the French LaRouge who was killed by Barnabas and his men is the "magical" and haunted spot that Barnabas uses as home base: "on the mound to the right , which was a forgotten chief's last show of pride , an old Frenchman had built him a log cabin , where he lived alone" (Thanet, p. 77). . . "Dick told them that he chose the place because it was a spot held accursed and haunted" (Thanet, p. 78). Conjuring is mentioned when Fairfax remembers tales he was told as a child to keep him in line: "How they terrified him! That one, of the big conjure-men who threw lizards into Mammy's mother so that she died-but that was not so frightful as the one about the little black cat without a head that would come and sit by a 'mean' boy's bed and purr and purr; and , if the boy should make the least bit of noise, would leap on the bed and rub its dreadful neck against him. What a ghastly fancy! Why must he remember it now?" (Thanet, p. 81). The "now" in question is when Barnabas takes him to LaRouge's ruins. "Aunt Tennie Marlow was well enough known to Fair. She was an old and very black negress who enjoyed a great name as a bone-setter, knew a heap' baout beastis,” ushered all the babies of the neighborhood into the world, and on the strength of these gifts and of living alone was suspected to be a “conjure woman" (Thanet, p. 163). To view all of my chapter summaries and highlights, click here.

0 Comments

Basic summary: This is an oddly cute story about a Governor at home who is approached by the mother of Fritz Jansen, a man sentenced to hang for the murder of his fiancee. The woman is German and speaks very little English. Luckily, the Governor's wife, Annie, is fluent in German. The woman tells of walking 15 miles to get to him before her son's execution. She asks for a pardon, as her son is a good man who would never do such a crime. Annie pleads with her husband to stay the execution--if he's truly guilty, why not give him a life sentence so his mother doesn't suffer. The Governor counters that to do so would be worse for Fritz's mother than executing him. If she hates the Governor, Very well , so be it . She will still have her memories of his youth to console her, and her very conviction of the injustice of his fate will be a comfort to her; while, on the other hand, if I release him, he will dissipate all her illusions, neglect her, ill-treat her, very likely spend every cent of her hard earnings, and at last convince even that trusting soul what a brute he is. It is the truest kindness to her to refuse." (Thanet, 299) The day after Fritz is hanged, the mother returns with her son, Fritz. It turns out there were two men with the same name, and her son was never arrested. Because he doesn't want to share the name with such a bad man, Fritz and his mother come to the Governor for a name change. Annie declares he'll change the name as a wedding gift to Greta and Fritz. The wedding is briefly described and the story ends with Annie and the Governor relieved at the outcome.

In the end, the Governor makes the comment that he would have been so embarassed if he'd followed Annie's "feminine" mind and pardoned the evil Fritz. He asks her who was right, and she exclaims, "Both of us" (Thanet, p. 299).

Basic Summary: Milt Bedford plans to take over Sycamore Ridge's post office and oust the former northerner named Captain Leidig, the current Postmaster. General Throckmorton can't bring himself to break the news to Leidig that he is being replaced. That night, the Great Fire breaks out, and Leidig and his "chemical engine" (Thanet, p. 273-4) save the post office and the town from the blaze. Leidig is gravely injured in the fire, and Throckmorton and the town think there is no way Leidig will be removed from his post after saving everything. Unfortunately, Bedford is installed as postmaster as Leidig is on bedrest and dying. His former assistant, Roz Miller, keeps up the charade that Leidig still holds the post, unable to break his heart as he lay dying. When Bedford intercepts a note to the office by Leidig before his assistant can, he goes to visit the ill-man whose job he took. He's tender-hearted enough to continue the charade and spares Leidig's feelings. The title of the story comes from General Throckmorton, the district's congressman. While citizens discuss how wonderful Leidig is as postmaster and how it's a shame he lost the post, Throckmorton says Leidig was an idiot to start with. Not only was he a humane officer in the military who treated political opponents well (Throckmorton being confederate military), but he also was brilliant and had patents. Had he kept inventing, he would have been rich. Instead, he was an idiot: Now I , gentlemen," said Throckmorton,“ I call Hiram Leidig a plumb idiot.” The crowd simply gasped; Throckmorton being Leidig's closest friend, and a man not to desert a friend under stress of weather, "Yes, gentlemen, a plumb idiot,” he repeated, in his gentlest tone; “here he is. He could have made a fortune had he stayed in the manufacturing business. When the war broke out he was getting a salary of twelve hundred dollars, and he had invented half a dozen little tricks, and got patents on them, and saved ten thousand dollars. . . Well, what does the government or the party give Leidig for his long services? You all know. Half a dozen times he has been within an ace of getting bounced by one party or the other, and now he is going to be pitched out in good earnest by his very own party because he can't be trusted to run the office as a party machine, and Milton Bedford can! That's the size of it. Now, a man who will squander his chances of fortune and the best years of his life on a government or a party which kicks fidelity every time is - a plumb idiot!" Themes: The North is not always the enemy and service is more important than wealth. We later find that Throckmorton "loved Leidig. The two men had been like brothers since the Federal soldier saved the Confederate soldier's life and cared for him in prison during the war" (Thanet, p. 268). When he confronts Leidig about his service and how he should have stayed in business, Leidig responds by saying: Look here, Marion, the way you felt for the South, I felt for my country, our country. [bold mine] And I had this kind of a feeling: the way to obliterate the war is to fetch people close together . You stay here awhile, old fellow,' says I, “and do your best for the old flag. Be a decent fellow, for they are going to sample the North by you. Don't go at them ramping and roaring, and shaking your opinions in their face like a red rag, when they're just naturally sore all over. Here's a chance,' says I, “ to do your country better service than you did in the war" (Thanet, p. 272). The story ends with the narrator suggesting that maybe Leidig was right about how it is an honor to serve, or "perhaps, again, he may be right some day" (Thanet, p. 284).

Notes: Roz Miller always takes Christmas week off, as he is "obliged" to get drunk that week. Leidig tells him that it's improper for a postman to be drunk, so every year, he suspends him that week. To keep up the ruse while Leidig is dying, he stays sober. We find out he also has a wooden leg, which is never explained, but French did later lose a leg due to complications from diabetes and was wheelchair bound in her later life in Davenport.

Basic summary: A tenant farmer is on trial for killing a con man. The case is up in Lawrence County (abbreviated as L---- County in the original text). The accused, Dock Muckwrath, shot a man who "changed cards" on him. The general public figure since Dock lost all of his money in the world ($50) the killing was justified.

The jury ultimately lets Muckwarth off--not because they think he's not guilty, but because the foreman reveals how horrible convict camps are: "The doctor , who had the medical eye for com plexion, observed that Captain Baz was certainly very pale . “ My opinion, sir," said the captain , slowly,“ is that, in the present state of convicts in Arkansas, if you don't find the man not guilty you had better find him guilty enough to be hanged" (Thanet, p. 239). He goes on to explain that, "He told me, what I found was true, that the whole convict system is a money-making affair. They are all on the make. The board, commissioners, contractors, lessees, wardens, and guards, — they all just naturally squeeze the convict" (Thanet, p. 242). Captain Baz Lemew relates how he was in one himself, and how he blew the whistle on the abuses in the camp by passing a note to an inspector's sister in town. The horrible abusive Warden Moss turns out to be the scoundrel Muckwrath shot. So, the jury looks at the case as one where justice was meted out by the killing. Characters of note: Mr. Phillipson: The prosecutor. He asks "why a State so beautiful, so fertile, so attractive to every class of emigrants, is neglected" (Thanet, p. 226) and argues "It is because the old taint of blood and crime clings to our garments still" (Thanet, p. 226) and that they must convict to ensure that other people realize "that there is not in all this broad land a more peaceful, law-abiding section than ours, or a section with better enforced laws" (Thanet, p. 226). His argument is important as there is a Northerner in the audience, as Dr. Redden says to the others: "Phillipson was right; it discouraged immigration. He had seen Mr. Thornton (the Northerner) in court. They all knew he was fixing to build a canning factory. Was he likely to do that if they convinced him that any of his men could get mad and pop away at him with a gun, sure of getting off? It looked like they might lose their factory, may be their railroad, if they monkeyed with the verdict. Let them remember their oaths and the law; that was all he asked" (Thanet, p. 235). Dock Muckwrath is described as: "His face was of a type common in Arkansas among the renters, where the loosely hung mouth will often seem to contradict fine brows, straight noses, and shapely heads. One could see that he was wearing his poor best in clothes, namely, a new ill-fitting brown coat, blue trousers, rubber boots, and a white shirt with a brass collar-button but no necktie" (Thanet, p. 225). Captain Baz Lemew: The jury foreman. Dock is one of his renters (sharecropper/tenant farmer), and during deliberations, we learn that he was once Trusty, No. 49. He is now married to the inspector's sister--the same one he passed the note to in town. Dr. Redden: "desired a conviction ardently. His motives were the cleanest in the world. Of the new South himself, he believed in immigration, enterprise, and their natural promoters, law and order" (Thanet, p. 222). Thornton: Northerner in attendance at the trial who is planning on building a cannery in L----- County. His reaction to the verdict: "The Northerner, who was with Phillipson, laughed outright. 'They do seem pleased,' said he. 'See, Phillipson, there go the interesting family home together in one of the jurymen's wagon; Muckwrath is kissing the baby. Well, I confess I am glad he does n't have to go to your confounded penitentiary" (Thanet, p. 261). Notes on setting: The town used to be prosperous, but the railroad passed it by. Now, it is struggling, hence the importance of Thornton's cannery coming. The court is held in Barker's store, as the courthouse burned down some time ago. Interesting mix of business and law, of course. Given that so many of her Arkansas stories take place in spaces where boundaries are blurry and often circles of influence overlap (a judge sees a citizen in his home, a store becomes a court, people live on plantations--the very epitome of business and personal life being merged--people are property). Also, next door to the court/store is the local bar, Milligan's. Notes on dialect/language use: Trusty=Trustee in today's parlance. Thanet's Arkansas stories often deal with race, and characters often use the "N" word when referring to people of color. This is problematic, but to consider the characters' use of the term as a sign of Thanet/French's own racism is simplistic, in much the same way that banning The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for Huck's early use of the word is problematic. We cannot fully explain Alice French's views on race on the characters' use of the word. That's not to excuse the use of the word entirely, nor is it to say that Alice French did not have racist views herself. It is--much like the issue of her being an anti-suffrage activist in real life while also having her own wood working shop, her own photography studio, and being coupled with another woman and being out in her Boston Marriage on an old plantation in Arkansas--complicated. |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed