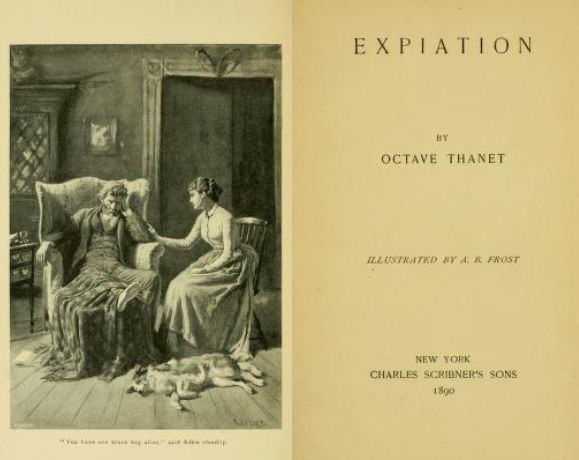

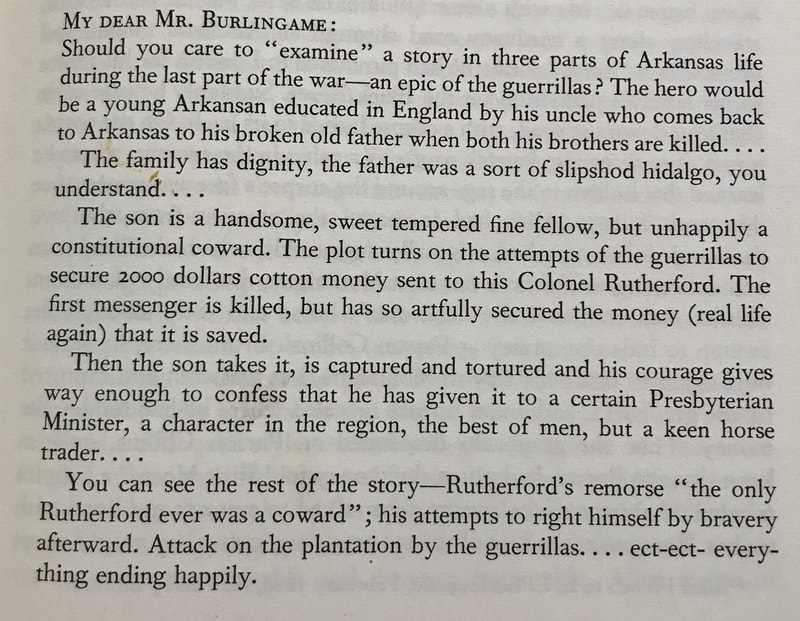

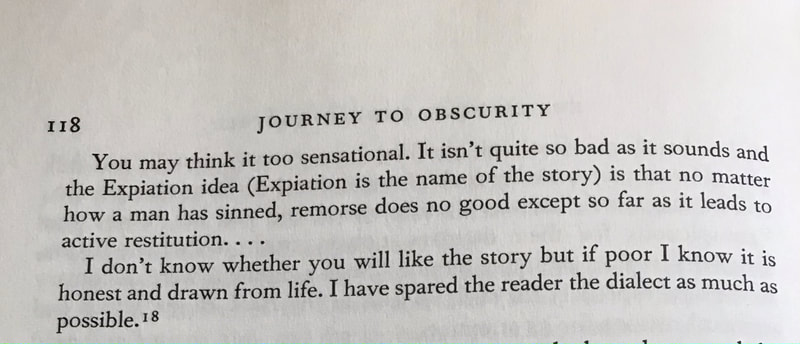

The summary in the above letter is spot on; the novel focuses on young Fairfax Rutherford, who has been living abroad with the uncle he was named for. He returns to his father's plantation in Arkansas and is immediately caught up on the robbery scheme and captured. His shame happens when he first reveals Parson Collins has the money; he feels guilty about revealing that, but is even more horrified when he thinks he's shot Collins after being burned with hot coals from the fire. The story works itself out; we later find that Collins is not only alive, but also that it wasn't Fairfax who shot him after all--it was Lige, who was aiming for Dick Barnabas, leader of the guerillas. Setting: The area around the Montaigne Plantation on the Black River. McMichaels notes it is set in 1864 (p. 118). Characters:

Expiation: Adele is the first to use the word "expiation" when talking to Fair about his guilt: "God won't hold you guilty for that. And even say you were guilty, guilty of the worst--well, what then? Does repentance mean despair or expiation? 'Bring forth fruits,' the apostle says, God will not despise a broken and a contrite heart: but if such a heart doesn't lead us to do something" (Thanet, p. 126). Adele continues on pages 127-128 to tell Fairfax he should stay in Arkansas and do right by Parson Collins: "you haven't any right to desert it. And because it is ruined and miserable, that's the more reason you should try to help. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country--stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends to Mr. Collins, to Unk ' Ralph—they love this poor country-stay here and help them try to save it. Oh, you know, you know how Unk ' Ralph has struggled to improve this place, to get better roads and better houses and some way civilize the people; and you know how Mr. Collins helped him. If you want to make amends--please, Cousin Fair, excuse the plain way I talk--then help to rid the country of the graybacks, and get in provisions, and keep peace now, and the rest will come in time . That —that will be expiation; [emphasis mine] but to lie here and die of shame—if you do , do you know what I say? Cousin Fair, you weren't a coward, but you are!" Masculinity: This is a central theme as Fairfax feels the need to fit his father's image of a real man. His brothers have died, and Fairfax is the sole heir left. When Barnabas says he was a coward, it crushes Fairfax and makes the relationship with his father strained (until the truth comes out). Fairfax is a bit of a dandy, but not necessarily in a bad way. While he has funny clothes and is softer than men in the Arkansas Swamps, those traits are not seen as a failing. At the end of the novel, his refinement is mentioned and becomes a bit of an issue for Adele who thinks she can never be quite refined enough for him, but Adele winds up liking his sense of fashion and his cleanliness. On page 81, we see that Fairfax was always sensitive to fear and that even as kids Adele had a stronger sense of rationality--see below regarding childhood tales of conjure men and headless cats. Adele didn't believe they were real, but Fairfax did. Race: Aunt Hizzie: She's treated as a caricature. "Aunt Hizzie, in her white turban (economically made out of a castaway flour-sack ), with a blue apron try ing to define a waist for her rotund shape, was always a figure in the gallery when dinner was under way" (Thanet, p. 30), Her method of communication is to holler at people. Barnabas: This issue comes up not only with Hizzie and other enslaved people of color in the book but also in terms of Dick Barnabas who is described as having a "sharp profile with thin lips, curved nose, hollow cheeks, a sweeping mustache, and inky locks of hair, straight and coarse enough to warrant the common taunt that 'all of Dick Barnabas wasn't Jew was mean Injun'" (Thanet, p. 66). Early on, Colonel Rutherford is telling his wife the story of Ma'y June and says, "Dick, he was renting of me then, am - mean Jew Injun, same like he is now, and getting most his livelihood swapping horses" (Thanet, p. 41). Thanet contrasts Barnabas and Fairfax: "Their eyes met; the cruel old-race black ones, the frank brown eyes of the Anglo-American; the glitter in each crossed under the torch-rays like sword-blades , but it was the brown flash that wavered" (Thanet, p. 75). Also, Thanet uses the word "injun" again when Lige tells Sam "he had a mind to kick, but he warn't no injun, by ____" (Thanet, p. 78). "in spite of his seeming apathy, Dick's Indian blood was at boiling-point. Lige stood in front of the open window; before he had time to realize the situation he found himself sprawling on the ground outside" (Thanet, p. 92). Magic of the Swamps: Mose has freedom to travel the swamps and communicates with animals. The homestead of the French LaRouge who was killed by Barnabas and his men is the "magical" and haunted spot that Barnabas uses as home base: "on the mound to the right , which was a forgotten chief's last show of pride , an old Frenchman had built him a log cabin , where he lived alone" (Thanet, p. 77). . . "Dick told them that he chose the place because it was a spot held accursed and haunted" (Thanet, p. 78). Conjuring is mentioned when Fairfax remembers tales he was told as a child to keep him in line: "How they terrified him! That one, of the big conjure-men who threw lizards into Mammy's mother so that she died-but that was not so frightful as the one about the little black cat without a head that would come and sit by a 'mean' boy's bed and purr and purr; and , if the boy should make the least bit of noise, would leap on the bed and rub its dreadful neck against him. What a ghastly fancy! Why must he remember it now?" (Thanet, p. 81). The "now" in question is when Barnabas takes him to LaRouge's ruins. "Aunt Tennie Marlow was well enough known to Fair. She was an old and very black negress who enjoyed a great name as a bone-setter, knew a heap' baout beastis,” ushered all the babies of the neighborhood into the world, and on the strength of these gifts and of living alone was suspected to be a “conjure woman" (Thanet, p. 163). To view all of my chapter summaries and highlights, click here.

0 Comments

Basic summary: The story opens with one-armed Jeff Griffin carrying home a tiny coffin for the recently dead baby of Cap'n Bulah, the love of his life (and distant cousin). Bulah is the widow of Sam Eller (the baby's father). Bulah still runs his boat, as she is determined to pay off his debts. When her baby dies, she is inconsolable. On his way to show her the coffin, Jeff picks up Nate who tells him about a baby left at the plantation store. The widow Mrs. Brand is caring for the baby, and Jeff picks her up and takes her to his house where Bulah is still rocking her dead child. When he sets the boy on the floor, he cries for his mother and Bulah shakes herself out of her stupor, allowing her own baby to be buried. Jeff and Bulah begin to care for the child in February. In October his mother, a traveling cotton picker, returns and demands her child back. The widow Brand saves the day when Headlights (real name Sabrina Mathews) tries to force the sheriff to tear the boy--now called Jeffy--from his foster parents. She demands board, cost of clothing, and cost of housing for the last eight months at a total of $27 to be paid in six months or Jeff and Bulah retain custody forever. Mr. Francis draws up a contract--thus, the "Mortgage on Jeffy." Headlights demands the right to pay the debt early. She returns when Jeffy has come down with a fever and they fear he'll develop pneumonia. He's always been puny, which was one of the reasons they refused to let her take him, as he would die without care he needs--care his mother can't give him on the road as part of a cotton-picking team. Jeff sees her in a stupor in the swamp and takes her home with him. Headlights realizes that she can't care for the child properly and makes Jeff and Bulah agree to marry and they can keep him. She develops pneumonia and dies. Before she does, she pulls a leather pouch from her neck and says it is for Jeffy. Inside is the $27 and a copy of the mortgage. Notes: I'm intrigued by the name "Headlights" here. It seems really odd. Also, I am not sure that this is as clearly sentimental or classist as McMichael seems to think. Headlights, just as with Dosier and Chaney before, has deep emotional feelings and ties to her son, even as she leaves him at 17 months at the store. Carrying a child that small from job to job couldn't be easy, and likely the child would have died. The whole mortgage situation is also weird. Obviously, Jeffy is not a slave or treated as property by Bulah and Jeff, but the idea of owning other people is definitely at play here. There's some weird "owning you to take care of you" stuff going on here (as in, you're being treated as property for your own good). |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed