|

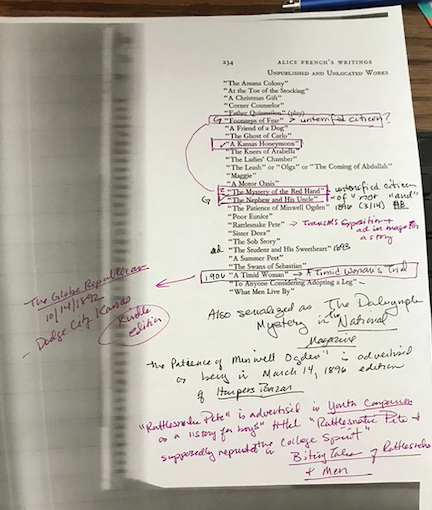

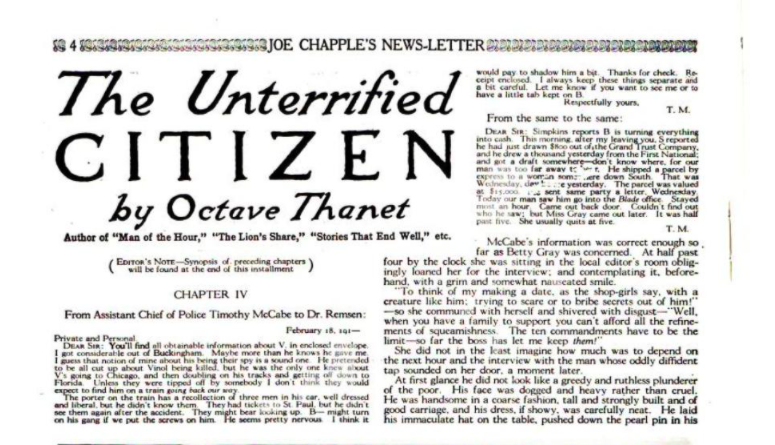

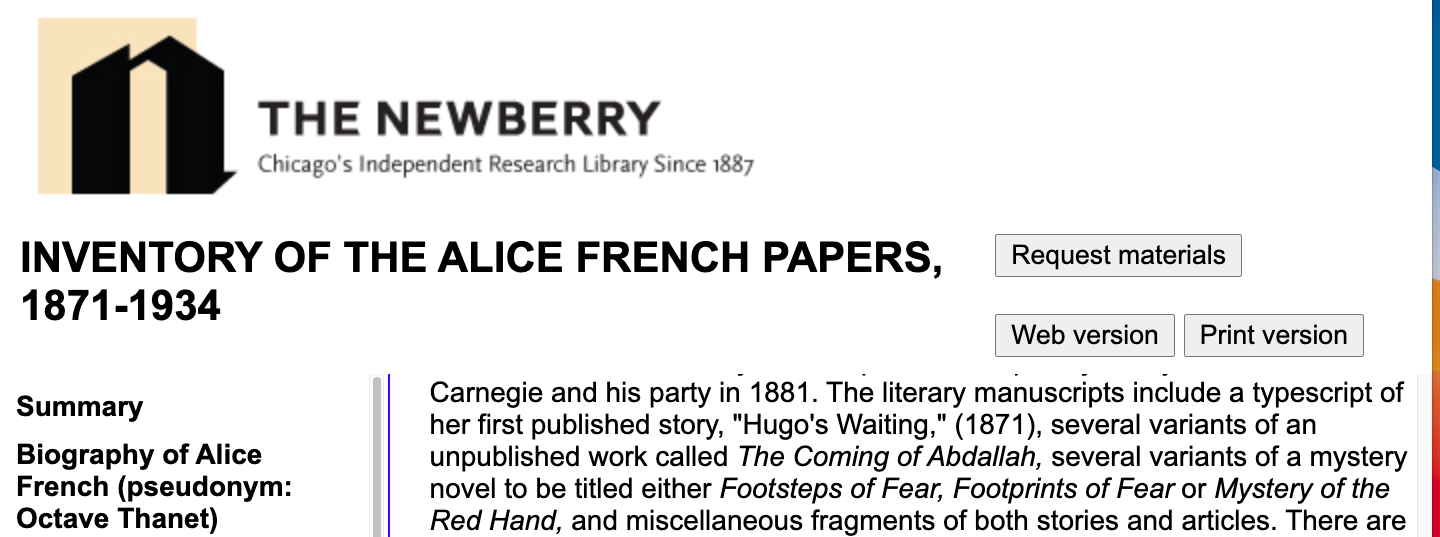

I've been using McMichael's biography to chart the timeline of Octave Thanet's stories, and yesterday, I realized there was a list in the back (see the photocopy I scribbled on above) indicating several texts he was unable to find in the 1960s. I went on the hunt to see what I could find digitally. My first find was "A Kansas Honeymoon" which was rereleased in Alfred Ludlow White's Short Stories: I also found some redundancies and errors in McMichael's list. Specifically, "The Nephew and His Uncle" should actually be "The Nephew of His Uncle" and "A Timid Woman" should be "A Timid Woman's Trial." I did find "A Timid Woman's Trial" on Amazon for 99 cents (snagged it) and found it in a Dodge City's The Globe Republican, from October 14, 1892. Ads for other stories like "Rattlesnake Pete and the College Spirit" (yet another inaccurately reported title from McMichael) showed up in publications like Youth's Companion as upcoming "stories for boys," but I have yet to successfully find a copy (If anyone out there finds a copy of Biting Tales of Rattlesnakes and Men by James William Jewell in PDF, let me know if that OT story is in there, ok?). I also spotted ads for "The Patience of Minwell Ogden" in the March 14, 1896 issue of Harper's Bazar (they still spelled it that way in 1896--that's not a typo). As luck would have it Cornell has the issue from March 7 and the one from March 21, but not for 3/14. Perhaps my most exciting find yesterday, though, started with this listing from the Newberry Library. I noticed the discussion of "several variants of a mystery," which was intriguing. Looking at McMichael's list, I see "Footsteps of Fear" and "The Mystery of the Red Hand" are listed separately. The Newberry seems to show them as variations of the same story, however.  And, as luck would have it, the ad for Chapple's News-letter seems to confirm that The Unterrified Citizen is a serialized version of "The Mystery of the Red Hand." Furthermore, I found The Dalrymple Mystery serialized in The National Magazine after it appeared in Chapple's. The opening chapter is the same.

So, not a bad haul for a day's work: that removes five "unlocated" entries on McMichael's list (and potentially six, if I ever find "Rattlesnake Pete and the College Spirit"). I did find an ad for "The Student and His Sweetheart" dated 1893, but have not found the text yet.

0 Comments

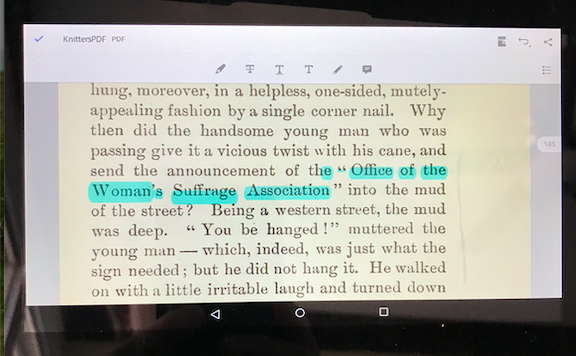

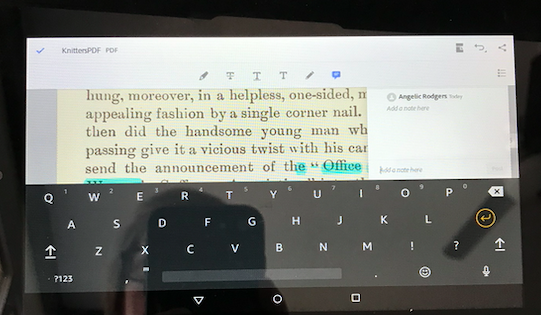

I debated whether to share this here, or in my regular old blog, but decided since the issue came up as part of my work on this project, it belongs here. One of the wonderful things about the digital age is that long-forgotten texts are often available as scanned first editions. This means that I can read the book as it looked to contemporary readers, which I find exciting. While I do own a few first editions of Octave Thanet's books, I don't (obviously) want to highlight and annotate the physical copies. So, I needed to come up with a solution. One option that appeared yesterday was to purchase an Onyx Nova 2 or 3 (the 3 just released and is available in color for $400+). Nova 2's run Android 9 and Nova 3's run Android 10. From the reviews I found this morning, they work well without taking forever to refresh when you turn the page, and you can search your notes. My problem is that our household already has multiple tablets, eReaders, and laptops (and a huge desktop). I've been using the iPad to read Knitters in the Sun, but wound up downloading in ePub so I could highlight and make notes to the text. The problem with that is that ePub and other converted formats contain tons of errors. While Knitters in the Sun is pretty "clean" as a converted text goes, the next one on my list isn't. So, I knew for my next read (and who knows how many others) that I would need to go back to the PDF scans. Using multiple devices to read and take notes is not appealing to me. Neither is shelling out another $300-$400 on another device. The reMarkable tablet allows me to "write" on the PDF but there's a horrible lag time when I turn a page. Adobe Digital Editions app allows me to see the scans and read, but again, there's a lag on turning pages and I can't annotate. The solution? Adobe Acrobat. I can't put it on the ancient iPad we have, but I do have Google Play on my Fire Tablets. And, Acrobat allows me to highlight, draw, and add typed notes to the original scans. Here's my 2015 Kindle Fire 7 inch with a note box open and some sample highlighting. I paid $50 for this tablet some five years ago and it still has great battery life, is less cumbersome than the iPad, and if it dies, I can easily afford to replace it. Update! After finding some texts only available at the Google Play store, I realized that the Google Play reading app also shows the scanned page and offers highlighting and notations. As a bonus, it saves those notes and highlights and syncs them with your Google Drive. In addition to the syncing, the highlighting is less choppy (neater) and the notes are easy to spot.

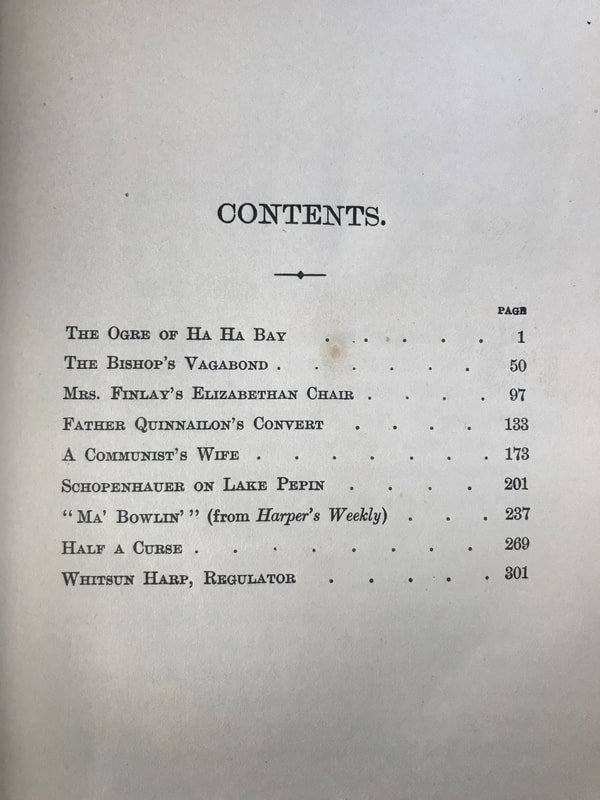

Louise (Bishop’s daughter) and Colonel Martin Talboys are talking at the start of the story. On pages 56 and 57, there’s a good bit of talk about the south. Specifically, Louise mentions that her experience of Southern manor houses and plantations has always been a bit of a letdown: I expected to see the real Southern mansions of the novelists, with enormous piazzas and Corinthian pillars and beautiful avenues; and the white-washed cabins of the negroes in the middle distance; and the planter, in a white linen suit and a wide sraw hat, sitting on the piazza drinking mint juleps. Well, I don’t really think I expected the planter, but I did hope for the house. Nothing of the kind. All I saw was a moderate-sized square house, with piazzas and a flat roof, all sadly in need of paint. Now, I’m like Betsey Prig; ‘I don’t believe there’s no sich person.’ It’s a myth, like the good old Southern cooking (p. 56). Martin assures her: Oh, they do exist . . .There are houses in Charleston and Beaufort and on the Lower Mississippi that suggest the novels; but, on the whole, I think the novelists have played us false. We expect to find the ruins of luxury and splendor and all that sort of thing in the South; put in point of fact there was very little luxury about Southern life. (p. 56). This exchange is interesting for multiple reasons. In terms of the story, Louise rejects Talboys in part because she finds him uninteresting and too short (the name is punny for that reason). Secondly, in Thanet’s own fiction, she more often focuses on the lower classes and those in rural Arkansas than she does any sort of idealized plantation imagery. The main plot summary: Demming (the vagabond) constantly lies and gets money out of Louise’s father, the Bishop. The story opens with such a lie about his wife dying and his need of a coffin. We find out, upon the Bishop, Louise, and Talboys visiting his cabin, that the wife is quite alive; the coffin was for a black neighbor, Mose Barnwell, whose wife had passed (p. 68). The Bishop and Demming make up, and it turns out that Demming has a relative in Charleston who has left him property and sent him money to travel there. After spending all of his money at the pub buying rounds, Demming is rescued by Talboys who is leaving town after Louise rejected him (Talboys buys Demming a new train ticket). The train collides with a freight train and in the wreck Demming breaks his leg. The bishop is trapped and no axe is on the train. Talboys runs to get one, and arrives just in time as Demming is prepared to shoot the bishop to prevent him from suffering. Talboys gets the bishop free, and the three return to Aiken. Demming has surgery to amputate his leg, but he dies after he patches things up between Louise and Talboys. Louise promises Demming that they will look after his wife. McMichael notes that the story is remarkable for the use of conventions of other local color fiction filled with romance and strange people in a unique setting, it was hardened with dialect that often required explanatory footnotes to lead readers through the jungles of apostrophes and phonetic approximations. It was Alice’s first use of extensive dialect transcriptions, and it revealed not only her attempts at realism but also the perseverance and tolerance that magazine writers and editors could expect from their readers (pp. 93-94). "The Ogre of Ha Ha Bay"

A newly married and honeymooning couple, Maurice and Susan, meet up with the Ogre and his nephew, Isadore Clovis, who is the carriage cab-man of sorts. The Ogre, Tremblay (p. 5), took a vow (p. 6) 25 years prior to never enter his new home until he takes a maiden of 20. Tremblay was engaged to the now widowed Madame Guion many years ago (p. 6), but she rejected him and married for love, rather than money, which we discover later. Tremblay arranges to marry her daughter, Melanie (p. 12). Melanie goes along with the plan, in part because Tremblay has always been kind to her and her mother. Melanie and Isadore are in love, but Tremblay has enough money to pay for her mother’s eye surgery, without which she will go blind. The interesting points of the story include the point of view (that the narrator is male and Thanet takes pleasure in describing Susan as the object of marital affection in the opening paragraphs and that Guion’s story of her marriage (p. 21) focuses on the discussion of domestic violence and hardship for women: It was twenty-five years ago, and M. Tremblay would marry me, but I was a fool, I: my heart was set on a young man of this parish, tall, strong, handsome. I quarreled with all my relations, I married him, M’sieu’. Within a month of our wedding day he broke my arm, twisting it to hurt me. He was the devil. Twice, but for his brother, he would have killed me. (Madame Guion to Maurice, p. 19) Domestic violence and marriage are both themes I plan to watch out for, as A Slave to Duty is a collection largely focused on those themes. “Love, it is pleasant, but marriage, that is another pair of sleeves” (21). The narrator reflects: But I thought that I understood the situation better. I believed Madame Guion told us the truth: she was only seeking her daughter’s happiness. She had an intense but narrow nature, and her life of toil, hard and busy thought it was, being also lonely and quiet, rather helped than hindered brooding over her sorrows. Her mind was of the true peasant type, the ideas came slowly and were tenacious of grip. Love had been ruin to her. It meant heartbreak, bodily anguish, the torture of impotent anger, and the bitterest humiliation.(Maurice, p. 23) The abusive relationships are off-set by the love of Susan and Maurice, the happy American couple (the story is set in Canada) who work at matchmaking and feud mending. In the end, Isadore sets fire to his uncle’s new house, figuring that if he has no new house, he has no reason to marry. In the end, Tremblay comes to his senses, embraces Melanie as his niece (after testing her to make sure she will still marry him) and pays for the Widow’s eye cure. In the end, the Widow is still opposed to the marriage between Isadore and Melanie, but they hope she’ll come around.

Gillette's "article takes up [Koppelman's] invitation and joins recent reappraisals of French's work by seeking to make more visible her contributions to gay and lesbian writing" (p. 141). Koppelman's inclusion of "My Lorelei: A Heidelberg Romance" in her 1994 collection Two Friends and Other Nineteenth-Century Lesbian Stories by American Women Writers was the springboard for Gillette's essay which covers "My Lorelei," "The Stout Miss Hopkins' Bicycle," and "The Rented House" as stories that challenge heteronormativity: a shared kiss between women in "My Lorelei," a challenge of body norms in "The Stout Miss Hopkins' Bicycle," and "heteronormativity as a form of body-snatching" (p. 140) in "The Rented House." What interests me about this recent article is that Gillette gives me hope that earlier criticism of Thanet (what little there is) was short-sighted: "But while French did indeed hold and espouse many conservative views, this narrow characterization of her life and writing omits too much. . . . Significantly, none of these readings match what we might expect a 'conservative' writer to write about. That the names Alice French and Jane Crawford have also begun to appear in gay and lesbian histories and chronologies and anthologies of gay and lesbian literature likewise suggests more to her writing than previously thought" (p. 141). Alice and Jane spent a lot of time together in their teens and early twenties, according to Gillette. In 1872, Jane married Joseph Crawford. Gillette mentions that McMichael assumed she was widowed, "the 1880 census, which found Jenny Crawford living at home with her parents. . .identifies her marital status with a D for divorced" (p. 143). By 1882, Alice and Jane had "rekindled" their relationship. While McMichael dismissed/ignored the romantic nature of Alice and Jane's relationship, Gillette uses Faderman's earlier (1981) discussion of Boston Marriages and examples from letters to show that McMichael's characterization of French's emotional letters as being "exaggerated" rather than romantic that he likely didn't have a full understanding of intimate female relationships.

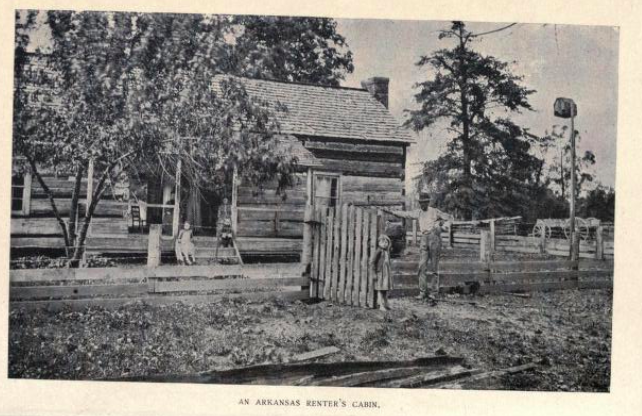

That's all I have to share today, but the news that Jane may have been divorced rather than widowed was a revelation. Gillette, Meg. "Keeping Queer Company in the Short Fiction of Alice French." American Literary Realism. Winter 2021: 53(2). pp. 138-158 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/amerlitereal.53.2.0138 My entertainment this morning is Octave Thanet's An Adventure in Photography, published in 1893. This book is for purchase, and I can snag a signed first edition for around $125 (granted, the description indicates it needs to be rebound) or an unsigned for $40. The book opens with a lovely indication of Octave and Jane's relationship, and the narrative parts of the book are a sweet glimpse into their home life and common interests, complete with dialogue. THPlenty of pictures here of Thanford and surrounding areas in Clover Bend, including this one, which strikes me on a personal level. My paternal grandfather was a tenant farmer in Arkansas. I have many reasons for my starts and stops on this project; understandably when it was necessary for me to work for other people during Dani's medical school and residency, I simply didn't have the time or emotional energy to work on it consistently.

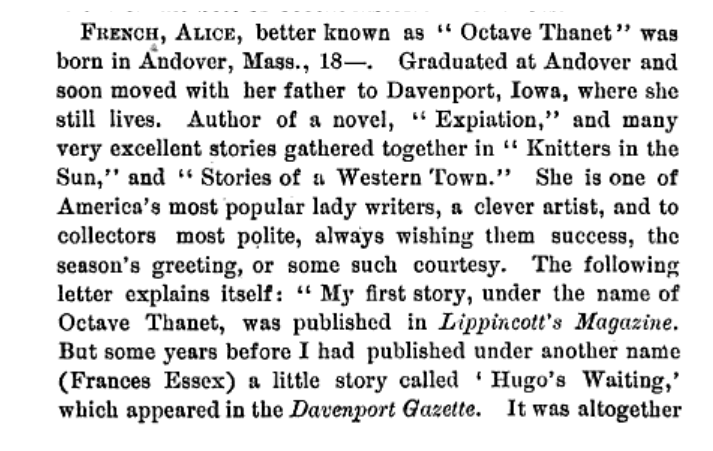

However, I'm also very aware that one factor contributing to the seventeen year gap between declaring I would pursue the project and yesterday when I finally sat down and started is that Octave Thanet is a contradictory character and there's a ton of things about her that are going to be uncomfortable. The very fact that she owned a plantation in Arkansas is prickly for me, as is her fairly well-documented anti-suffrage position. But, that's the goal of this journey--to figure her out. Her one published biography is older than I am, after all, and perhaps a fellow lesbian and Arkansan by choice can add to our understanding of her life and how she lived it. The first published story by Alice French was published in the Davenport Gazette in February 1871 under the pseudonym Frances Essex. In the only currently existing biography of French, George McMichael's 1965 Journey to Obscurity: The Life of Octave Thanet, McMichael notes "The manuscript remained among her papers after her death. Her mother had written on it 'This is Alice's first published story.'" (note on page 43). I also send that little story I read so long ago to you. . .Do you remember it? Mr. Sanders wanted something for this Saturday's Gazette, so I finished up that. It is very stupid, I know, but it was written for the popular taste, which is also stupid. While the manuscript is among French's papers, her statements about that story clearly indicate why I can't find a digital copy today. McMichael suggests that the paper likely published it because the editor "was a friend of Alice's father and knew the virtues of local authors" (McMichael, 43).

You can check out the biography, which is a published version of McMichael's dissertation, at the Internet Archive if you have an account. My first encounter with Octave Thanet/Alice French was the four paragraphs in Lilian Faderman's classic work Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women From the Renaissance to the Present: In America the author Alice French, who wrote under the name Octave Thanet, and Jane Crawford, her companion of almost half a century, also had a relationship in which the energies of both went into the career of one. Octave, who for thirty years was among the highest paid writers in the United States, also came to literature as a business--and her success in it was due at least in part to the nurturing support that Jane gave her. Thanet's success and her relationship with Crawford would be enough to gain my interest; after all, my dissertation focuses on three-named female writers who may or may not have been lesbians who were highly successful and are all but forgotten: Mary Wilkins Freeman, Sarah Orne Jewett, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Sure, we all read a single short story by these women in our American Literature surveys, but they were as successful or more so than their contemporary male writers like Twain, Hawthorne, and Melville. Add to the mix here that Thanet and Crawford owned a property in Clover Bend, Arkansas that they named "Thanford" and that Alice/Octave was anti-suffrage, worked in her woodshop, was a skilled photographer, and, according to Faderman, "seemed to view humanity as having three sexes--men, women, and Octave Thanet" how could I not go on a voyage to figure Octave Thanet out?

And, on the morning I decided to start, what do I see but an article "Keeping Queer Company in the Short Fiction of Alice French" by Meg Gillette in the most recent issue of American Literary Realism. So, old Alice is getting other folks' attention too. I'll be starting my primary text reading with Knitters in the Sun, her collection from 1887. While I have the copy pictured below, I'll be using the scanned text to save my first edition. |

About this project:I've been saying since 2004 that I was going to write a critical biography of Octave Thanet (Alice French). This blog is the start of that work and will include notes, links to research, and other OT related tidbits. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed